OSS17-0913/1030FW102-4 – A Guide to the Films of Shane Black: Part 4

“And sometimes…sometimes, you just win.”

– Holland March, The Nice Guys

In the two decades between selling his screenplay for The Long Kiss Goodnight in 1994 and wrapping on Iron Man Three in January 2013, Shane Black wrote and directed Kiss Kiss Bang Bang and that’s it. Consider this context: at the time Black was withdrawing from making movies – retreating to his mansion, his drugs, his parties, and, indeed, his mansion drugs parties; keeping in touch, barely, through new mentor James L. Brooks; and later, as the new decade began, and for years on end, drinking and brooding – Stargate had just become the first Hollywood release to have a website. By the time Black found sobriety and returned for good, many films could be watched on a website. Shane Black’s retirement coincided with the most profound technological leap in communication in human history. YouTube predates his return, for goodness’ sake. Even Terrence Malick didn’t miss this much.

During Black’s first, decade-long lacuna, the Internet transitioned from dial-up, Altavista, GeoCities, pages that loaded scattered with failed image Xs, something your school had on one computer only, something 13-year-olds barely considered; to broadband as standard, Google, MySpace, Limewire, something in every home, something integral to school and workplace.

And in the seven or eight years between his directorial debut Kiss Kiss Bang Bang and his unlikely and colossal sophomore effort Iron Man Three, further exponential innovation saw the internet leap from laptop to tablet, tablet to phone while at the same time, first films and then arguably cinema itself moved online. I’m fascinated that, in professional terms, Black simply missed all this. He ducked out at laserdisc and by the time he got back we were streaming. Career-wise, he’s a chrononaut.

Black’s hiatus also ran concurrent with my own maturation from cineaste boy to cineaste teenager (I’m reticent to suggest I’m yet cineaste man), a growth in which the internet was essential. After five years of TV listings and four year of Halliwell’s and three years reading Empire and 12 months with Total Film, too, by the Millennium it was the IMDb that had become my default source for movie research, that I was poring over daily during free periods, from which I was saving pages to floppy to archive at home. My pathetically vivid memory of trawling Ben Stiller’s filmography and first reading the name “Bob Odenkirk” has outlasted the library, the building and indeed the school in which that memory was formed.

Information had grown faster than print and I was moving with that same agility. At uni, I was consuming new bands so far ahead of the mainstream it became alienating, and on IMDb, tracking films for months and years as they confirmed directors, added actors, announced shooting dates, all of this 12 months, 18 months, 24 months before anything pitched up in cinemas.

Black’s page was as encased in amber. For years, the only movement was the release date of the inscrutable A.W.O.L., to the point where whatever A.W.O.L. was, I presumed it probably didn’t physically exist, nor may it ever, like the Coens’ To the White Sea. Long before I caught up with him, this feller Black had been touted as a shit-eating-grin Hollywood hotshot millionaire, though by now scant evidence remained for me to comprehend this reputation. One – who was this guy, two – where did he go?

Black was nowhere. His apparent retirement was sufficiently prolonged that in the time he was away I earned every educational qualification I possess. He missed my adolescence entirely. Unlike the ‘70s-born generation that preceded mine (and, as it happens, the ‘90s-born generation that followed mine), my cohort’s Friday night flicks couldn’t benefit from Black’s wit and maturity, his remarkable, heartfelt melding of humane characters gasping for air in inhumane worlds. Instead, at the turn of the century action cinema was increasingly dominated by accessible, teen-oriented adventures written by David Koepp, Zak Penn, Elliott & Rossio, Gough & Millar. Polished computerized capers of considerable contemporary enjoyment, but largely juvenile and ultimately meaningless. Films which decimate city blocks and lay waste to armies but can’t show a punch connecting. Nothing meant anything, and so it continued.

Within this gaudy maelstrom of superheroes and pirates, I grew to love, if not grasp, The Last Boy Scout and The Long Kiss Goodnight. In his absence, Black became iconic to me, like Malick, Martin Brest, John Hughes. It’s comfortable – and juvenile – to develop particular fondness for something that doesn’t change. Every so often I visited that IMDb page, like Dave Toschi parked at Washington & Cherry. I pondered the fate of the superstar screenwriter who had disappeared far beyond the reach of ones and zeroes.

School finished, Sixth Form finished, uni finished. The acuity of my recollection of Black’s return to cinemas is as an apartment shot by Tony Scott, and I’m Brad Pitt’s Floyd – present, but only tangentially participating. I had met Luke. I was arguably employed. I’m at a loss to remember what I ever ate, beyond Pasta ‘n’ Sauce with cherry tomatoes and a slice of packet cheese. Norwich felt dark, and oppressively damp. I better remember seeing The New World utterly dizzy with ’flu, or walking home underwhelmed by Haggis’ Crash, than I do making the same journey back from Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. But I’d been tracking it for months, unconvinced it was really happening, with little idea of what to expect, and as close to opening night as possible I was definitely there and definitely dazzled, though now I can concede my enjoyment was still too superficial, that I still lacked the tools to interpret the depth of the film’s accomplish. Fortunately, I had eight years to grow up before Iron Man Three.

The triptych that form Shane Black’s second act effectively reboot him entirely from spec-script Gen X enfant terrible to producer-protected writer-director, with a consistent tone and viewpoint felt even when working commercially. Shorn of the overt studio gloss of Donner and Scott or the action bombast of McTiernan and Harlin, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang and The Nice Guys reveal Black as what he always was – a creator of streamlined, self-knowing, real world detective noir, just like the paperbacks his old man brought him up on.

In both that milieu, so prone to hyperbole and Tarantino-esque indulgence, and when working within the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Black’s work is grounded, and all the more affecting for its wry but uncompromising reflection of how people, not characters, behave. His locales and their inhabitants are so amoral that their litany of corruptions and obscenities were long since waved through for sake of convenience – in The Nice Guys, the very air is poison.

Our nominal heroes have already been reluctantly rendered resilient to this reality – Kiss Kiss Bang Bang’s Gay Perry and Harmony and The Nice Guys’ titular Healy and March. Those that haven’t must actively overcome their repulsion and distress just to survive. In Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, a hiding Harry Lockhart witnesses a Hollywood stray suddenly gunned down inches from his fingertips. His only recourse is to first shush her dying breaths to avoid being found himself, and that about sums it up. This isn’t shades of grey, it’s shades of Black, and this is Part 4 of our guide to his films.

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (Black, 2005)

written by Shane (cribbed from a book by Davis Dresser), produced by Joel Silver

Does the title begin with an L?

No, but it has “kiss” TWICE.

Is it set at Christmas?

Opening scene:

MUSIC CUE: “‘Sleigh Ride”

NARRATOR (V.O.): It’s hard to believe it was just last Christmas that me and Harmony changed the world.

Kidnap?

Yep. Torture, too.

Blackmail?

Buried in there somewhere, yeah.

Mismatched partners?

Permanently foot-in-mouth petty thief Harry Lockhart (Robert Downey, Jr) is transplanted to LA on a whim by a movie producer impressed with the entirely accidental Method-style authenticity Lockhart conveys in a casting call he crashes while fleeing the fuzz. Looking to drive down Colin Farrell’s asking price, the studio sets out to create a buzz around novice Harry, and for some real-world experience pairs him with veteran Hollywood PI “Gay” Perry (Val Kilmer). This is all established in the first nine minutes, and if you think that character conspectus is convoluted, buckle up – the plot itself is as complex as The Big Sleep.

Note: At the time of release, at the time of my first draft in 2017, and likely even now, Val Kilmer’s Perry van Shrike is the only gay male lead or co-lead in any action-oriented Hollywood movie, ever.

Post-traumatic Shane disorder?

All three leads and, according to the film’s theme, most of the women in Hollywood were screwed up, long before adulthood, by bastard men.

Fallen angel?

Never-was actress Harmony Lane (Michelle Monaghan), a welcome blast from Harry’s past, pragmatic but still romantic, streetwise but not embittered.

Also: her abused sister, Jenna; ephemeral Hollywood scion Veronica Dexter; and by implication, most all of the females Harry meets, at least according to Harry: “These are damaged goods, every one of them, from way back… It’s abandonment, it’s abuse… I mean, it’s literally like someone took America by the East Coast and shook it, and all the normal girls managed to hang on.”

Shane, by this time openly contemptuous of “Hollywood women” and his experience of them – in his own words, “I’m cynical about the type of girl that swirls in the Hollywood community” – is intent on making an interesting though pessimistic point, but does still incorporate a rebuke: Harmony asks, “Alright – everyone who hates Harry here, raise your hand”, and the entire room responds. Inherent in the criticism, too, is an understanding and empathy for the type of people Hollywood attracts – vulnerable nobodies escaping nowhere towns, desperate for validation from strangers.

Trash-talking teen?

Nope, with a but – Harry has an excitable niece back in New York with whom he chats on the phone. (His own narration would no doubt mock the screenplay’s use of such an obvious humanising device.)

Domestic bliss?

Perry: How about you, Harry, did your father love you?

Harry: Ah, sometimes, like when I dressed up like a bottle. How about yours?

Perry: Well, he used to beat me in Morse code, so it’s possible, but he never actually said the words.

Convoluted conspiracy?

I’ve seen this film five times and still there’s elements that haven’t stuck. Broadly, events are dictated by the criminal indiscretions of two shit fathers and the lies, both malign and ameliorating, their appalling behaviour necessitates. Thematically, poisonous patriarchy is pivotal. But I swear the entire plot hinges on a seemingly minor disclosure tossed off in a single line of dialogue about six minutes in.

Scene-stealing henchman?

The two goons credited as Mr Frying Pan and Mr Fire feel too much like someone who isn’t Shane Black trying to write henchmen like Shane Black.

Brilliant second-baddie?

Not in this one, in fact there’s rather an antagonist vacuum. The real villains are manifestly the abusive fathers who set these broken characters on their paths to La La Land.

And who was actually the baddie?

Corbin Bernsen, barely in it, and looking very much like Patrick Malahide.

None more Black I

Z-movie actress: So, what do you do for a living?

Harry: Oh, I’m retired. I invented dice when I was a kid.

None more Black II

Harry’s first encounter with Harmony occurs at a party when he walks in on her asleep as a nameless LA prick ponders how he’s going to rape her.

Harry interrupts and dispenses a few pithy hard-boiled threats – “Do not think. Walk the fuck away, or let’s me and you go outside right now. It’s past my bedtime. Make a choice.” Cut to:

the front lawn – models watch impassively as Harry has the shit kicked out of him.

They’ve read all the books and seen all the movies I

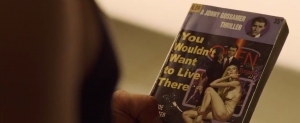

The film is presented in chapters with names ripped straight from Chandler – “Trouble is My Business”, “The Lady in the Lake”- and the plot itself is driven by its characters’ love for a series of vice-laden pulp detective paperbacks starring Jonny Gossamer.

They’ve read all the books and seen all the movies II

Protagonist Harry’s narration is so meta it’s more like a DVD commentary – addressing the audience, deconstructing the narrative, criticising the edit, at points literally stopping the film to rewind, jump forward, redo. In one instance, he directly apologises for the preceding scene of innocuous exposition: “That was terrible. It’s like, ‘Why was that in the movie? Gee, you think maybe it will come back later? Maybe?’ I hate that. It’s like that shot of the cook in The Hunt for Red October.” Its eventual resolution is a rambling to-camera wrap-up post-epilogue, mercifully curtailed by Gay Perry.

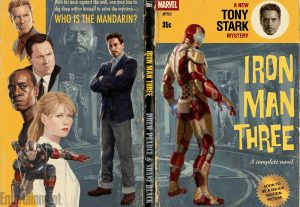

Iron Man Three (Black, 2013)

written by Shane and Drew Pearce

Shane’s entirely successful blockbuster directorial debut. Seven years later, still in the top 20 biggest grossers of all time. Sixteen films later, still comfortably in the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s best three outings.

Black and Joel Silver rolled the dice on a recovering Robert Downey as their lead on Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang and when the time came, Downey repaid the favour and then some, and without completely denying any of his director’s idiosyncrasies.

From the very beginning, this is identifiably a Shane Black joint – its opening narration, redolent of The Long Kiss Goodnight and Mike the Detective, could even be a continuation of Kiss Kiss Bang Bang’s playful coda – and though the verbiage doesn’t vibrate with the usual panache, it retains his central thematic concerns: emotional trauma, moral corruption, venal institutions, and historic sins reverberating in the present.

Does the title begin with an L?

Nowhere near, but then Lion Man sounds more like a documentary by Werner Herzog.

Is it set at Christmas?

It is, and there’s even a flashback set on Millennium Eve!

Kidnap?

Naturally.

Blackmail?

Slattery: Ah, well, I had a little problem with… substances…Then, they approached me about the role, and they knew about the drugs…

Tony: What did they say, they’d get you off them?

Slattery: Said they’d give me more!

Mismatched partners?

Takes a while, because they’re separated for most of the picture, but when the “House Party protocol” kicks off on that oil tanker you realise Tony & Rhodey are totally Riggs & Murtaugh.

Post-traumatic Shane disorder?

Unusually for a superhero sequel, but entirely predictably for a film written by Black, characters and the world they inhabit deal directly and realistically with the emotional ramifications of the previous entry’s events, in this case the Gotterdamerung of the Battle of New York seen in preceding MCU picture The Avengers. After flying through a wormhole and back in a literal and metaphorical resurrection, Tony Stark is, quite understandably, fucked up.

Fallen angel?

Maya Hansen, a thoroughly welcome Rebecca Hall, whose role was regrettably reconditioned during the shoot from lead antagonist to lackey with split loyalties.

It’s particularly galling that we were robbed of a female Black baddie because Marvel, that most progressive of studios, believed that casting a woman as the villain was not concordant with the commercial goals of its corporate strategy. (Retrospectively, culpability has been assigned to – quelle surprise – departed CEO and controversy-magnet Ike Perlmutter.) At least Gwyneth gets to do some stuff.

Trash-talking teen?

Ty Simpkins carries a well-developed, typically unsentimental pit-stop in small town USA as a likeable latchkey urchin with a waitress mom and a dad who “went to 7/11 to get scratchers – I guess he won, cos that was six years ago.”

Domestic bliss?

As with most central couples in a Shane Black movie, man is an emotionally frazzled mess wedded to his work and woman is far too capable to be sticking around much longer.

Convoluted conspiracy?

A tech genius jilted by Tony 13 years prior has returned revitalised and ready to disrupt world orders in alliance with super-soldiers, the usual treacherous politicos and a gnomic terrorist for the YouTube generation.

Scene-stealing henchman?

James Badge Dale, excellent as ever, playing a bomb man.

Brilliant second-baddie?

Sir Ben Kingsley’s ripped-from-the-headlines terror preacher, the Mandarin, and just in case you ain’t seen the thing we shan’t say any more than that.

And who was actually the baddie?

Pitiably greasy science nerd-turned-sexy boy Guy Pearce and his hollow cheeks.

They’ve read all the books and seen all the movies I

Killian: “Ever since that big dude with the hammer fell out of the sky, subtlety’s kinda had its day.”

None more Black I

Tony: You walked right into this one: I’ve dated hotter chicks than you.

Brandt: Is that all you’ve got? A cheap trick and a cheesy one-liner?

Tony: Sweetheart, that could be the name of my autobiography.

None more Black II

Surrendering henchman: Honestly – I hate working here, they are so weird.

The Nice Guys (Black, 2016)

written by Shane and Anthony Bagarozzi, produced by Joel Silver

Does the title begin with an L?

Sadly not. Shall we call it “The Lovely Lads”?

Is it set at Christmas?

Keep watchin’…

Kidnap?

Nope.

Blackmail?

Full of it.

Mismatched partners?

Jackson Healy (Russell Crowe) is an ageing, affable bottom-rung enforcer, notable only for 15 minutes of fame after foiling a restaurant robbery. Holland March (Ryan Gosling) is an easily aggravated, ineffectual dipsomaniac widower and father who makes a surprisingly good living as a PI shaking down geriatrics. They meet when Healy makes a housecall to break Holland’s arm. Both men exercise a pragmatic relationship with morality.

Post-traumatic Shane disorder?

As usual, Black’s tragicomedy rather creeps up on you – the chucklesome naughtiness of a 13-year-old habitually given to act as her father’s chauffeur is painted far darker as it becomes clear she has to ferry him around because her mother’s death from cancer has made him a benign but hopeless drunk.

Jackson: I didn’t know what time you’d get here. You said afternoon.

Holland: Well, uh, we were at the bank, getting your money.

Holly: (with resignation) We stopped at a bar.

Fallen angel?

Recalling Lethal Weapon, the conspiracy begins with a doomed waif in her sports car careening down a hillside and smashing through a suburban home before quietly expiring. Margaret Qualley’s ingenue crusader Amelia soon picks up the plot and runs with it, through a poisonous culture of sex-toy women inured to their own mistreatment and the amoral males that use them. It’s a place that leaves March despairing – “It’s over. The days of ladies and gentlemen are over. This is what Holly’s looking down the barrel of.”

Trash-talking teen?

In abundance. In addition to Holland’s grown-up-fast daughter Holly (Angourie Rice) – speaking to her father, “You’re the world’s worst detective” – highlights include Lance Butler as that fucking kid on a bike.

Domestic bliss?

Recalling the mantra of Joe Hallenbeck, March has written on his hand, “You will never be happy.” His wife died in a gas fire he couldn’t prevent, leaving him to slide into alcoholism in front of his compassionate but angrily despairing daughter. Healy’s old lady split with Healy’s fucking father – “He accepted her betrayal with ‘equanimity’.”

Convoluted conspiracy?

As in The Last Boy Scout, the black heart of the piece is a corrupted American institution from which modernisation is antithetical – Detroit’s Big Three, which has colluded with a corrupt DoJ official to suppress the catalytic converter, a conspiracy about to be made public by that official’s rebelling environmentalist daughter and her expose, which takes the form of an “experimental film” (read: porno).

Scene-stealing henchman?

As chocka as The Last Boy Scout, with particular plaudits going to beautiful, beautiful Matt Bomer’s icy “John Boy” and his nonchalant, “That sound? Oh yeah, just now. That was me. I threw that little girl out the window.”

Brilliant second-baddie?

Opts instead to ante-up on the bit-part hoods, with a murderer’s row of hitmen adorned in period-appropriate garish attire and attitudes.

And who was actually the baddie?

Kim Basinger, barely in it.

None more Black I

“Look, if you come in here, you beat up on me, you trash the place, I understand, it’s part of the job. I accept it. But what did you do? You did something different from that, didn’t you? You pissed me off. You made an enemy. Now, even if I knew something, I wouldn’t tell you, kid. And you know why I wouldn’t tell you? And this is… It’s not my only reason, but it is a principled reason. I wouldn’t tell you cos you’re a fucking moron.”

None more Black II

Twisting around the knockabout capering is a thick streak of sobering fatalism, especially as it relates to females, who throughout suffer appropriately shocking spasms of violence. Noir is a tough place to be a dame, and the cruelties of Lost Angeles, in Black’s words “a smog-laden porn pit”, is no place to be a lady.

His protagonists are fuck-ups, and anachronistic in their own time, but like the private dicks of ‘40s pulp fiction they remain men of compassion and lingering decency, and a counterpoint to the degradation that swirls about them.

As for the females whose dignities they hope to preserve, however square and hopeless that pursuit may seem, Black is equally realistic but optimistic – the world has degenerated into a fucking mess, yes, but at least its earnest, capable, desperate youth are feverishly trying to clean it up. Thunberg would dig this flick the most.

None more Black III

The picture opens with a helicopter shot that crests the Hollywood sign:

dilapidated, aching with graffiti, literally falling apart, a crass advertisement still reflecting its original purpose but now as a grim pastiche. How’s that for symbolism?

Further reading: Part 1 of our Spotter’s Guide focuses on The Monster Squad and Lethal Weapon; in Part 2 we duck and cover as Black blows up with Lethal Weapon 2, The Last Boy Scout and Last Action Hero; and Part 3 considers the price of pain in the world of Shane Black and discusses his first masterpiece, The Long Kiss Goodnight.

Further listening: we discuss what’s Black, Blacker and Blackest with an ’80s Shane Black marathon; and reflect on Predators old and new.