As Covid-19 lockdown (sort of) eases in (parts of) the UK, Fletcher Walton and Luke Littleboy review how they’ve been feeling and what they’ve been watching in lieu of going to the flicks.

“Time Enough At Last”

by Fletcher Walton

The last film I saw at the cinema is one that doesn’t exist.

Back in February, I was delighted to catch an invitation to a test screening. Studios run test screenings for new films several months ahead of scheduled release in order to guide reshoots, fine tune a final cut, or identify an audience around which to develop marketing – the practice has become common, and no indicator either way of the quality of the project being tested. The cinema release for the much-anticipated movie I saw was planned for this autumn – unsurprisingly, that’s no longer on the cards. Though at least long-postponed reshoots recently wrapped, XXXX XXXXX XX XXXX [You should check the statute of limitations on that NDA, we might be alright. – LL] is now opening in spring 2021, which means that half a year ago I watched a film that doesn’t come out for at least another six months. Er.

A week after that test screening, I was primed for my usual post-awards season catch-up shuttle runs between the Watermans in Brentford and the Regent Street Cinema at Oxford Circus but a lingering lurgy likely contracted from The Strokes at the Roundhouse (that is, the crowd in attendance, not literally Jules et al) put the kibosh on my diary dates for Parasite and A Hidden Life and The Lighthouse, and the nationwide release of The True History of the Kelly Gang, too. First weekend of March, cinema was forsaken in favour of a blissfully rural Norfolk sojourn with the Littleboys. [You owe me a pizza. – LL] And the following Friday, Fulham v Brentford was postponed at eight hours’ notice and truly the pandemic and its closures were upon us.

At the end of August when I take in Nolan’s Tenet, it will be my first trip to the flicks in 28 weeks. That’s the longest hiatus since 1998. Similarly, in my capacity as a Fulham fan I haven’t been so long between matches since the 2003/04 season I missed entirely when I was living in California. The joy and release and beaming satisfaction of sealing promotion in extra time of the play-off final of the longest Championship year ever completed has been crucially dampened by not being able to see it happen or celebrate it among the people with whom it should be shared.

None of us will be back at the Cottage for the not-so-big kick-off in September, either. [In contrast, speaking as a match-going Town fan – long live the bloody lockdown! – LL]

For most of this century, as a student and then a shift worker, it’s been football and cinema that have provided routine and structure to my weeks, months and years. How acutely trying that the crisis we face today should be one characterised by the removal of these two comforting, nourishing, communal weekly waypoints. These diary staples prevailed and thrived across four generations and through two world wars. Even during the eight months of the Blitz across more than a dozen UK towns and cities, even during the nine weeks of 1940 in which London was bombed 56 out of 57 days, our grandparents and great-grandparents still had the pictures on a Friday and the football at the weekend. How disconcerting that for almost half a year now we’ve turned a new leaf on the calendar to find yet another month of Thursdays.

I’ve found lockdown satisfactions in lasers and tapes, Freaks and Geeks and Eastbound and Down, breakfast on the balcony with Julia Phillips, afternoon ball throw in the park and late-night runs on quietened streets. And yet, five months on – or, more worryingly, in – doing nothing hasn’t been as easy as it sounds. I shall be very pleased indeed to meet my pals, share a meal and together enjoy a movie.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail; Monty Python’s Life of Brian; Brazil

(Terrys, 1975; Terry Jones, 1979; Terry Gilliam, 1985)

Brazil has been a much-watched favourite since I received the Criterion mega-set on LD some nine years ago, but what a pleasure to return to Holy Grail and Life of Brian for the first time in perhaps 15 years and find both have if anything improved with age.

Holy Grail remains a visually arresting, formally audacious, genre-defining comic delight. Arresting, because of the almost pungent documentary realism of its locations and their suitably sodden denizens – if only modern comedy gave one tenth of a shit about set dressing and photography, eh? Audacious, because it reflects the Pythons’ roots in the madcap, sometimes inscrutable satire of the ‘60s (Dick Lester, Terry Southern, whatever Spike Milligan was up to) that presaged the more accessible and more successful absurd deconstructionism of Flying Circus. Here, the fourth wall is not so much broken as never erected. Even the opening credits undermine convention before collapsing into nonsense.

The film is a comedic keep that has proven impregnable for 50 years, and the principles of its construction remain industry standard.

If Holy Grail ably summarises the preceding decade of British comedy, and sets a template for irreverence to subject and medium still used today, Life of Brian seems instead to comment directly on the present – not just its present, but right bleeding now. The contemporary regression by the novel illiberal alt-left toward the most insular and impractical excesses of Western socialist politicking – led in part by the very same thoughts and thinkers the Pythons were criticising 40 years ago – has embarrassingly but enjoyably rendered Life of Brian as relevant as ever in its central lampooning of self-defeating internecine squabbles and the inertia of a leftist bureaucracy that prevents its insurrectionists from ever actually getting round to fighting the common enemy. [Aaand breathe. – LL]

In particular, its digression on a man’s inalienable theoretical right to bear a child (“We shall fight the oppressors for your right to have babies, brother. Sorry, sister.”) feels so current as to be ripped from tomorrow’s headlines – but demonstrates that the apparently fresh preoccupations that so vex us today may not be so new after all.

Brazil follows Brian’s tragic ironies and focuses even more intently on the Orwellian terror of a closet non-conformist increasingly tangled up in rebellion and ultimately crushed by the system, a theme director Terry Gilliam has also found himself exploring in his own real life as often as possible.

All three films benefit immeasurably from the tactile reality of Gilliam’s production design. The squelching mud and mildewed castles of Dark Ages Britain, heavy with mist and “covered in shit”. The sun-baked limestone and torchlit interiors of bustling Judea. The oppressive geometry and creaking machineries of a dreadfully British inter-war dystopian metropolis.

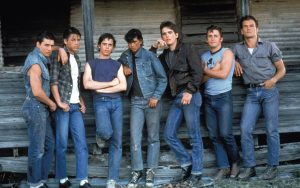

The Outsiders: The Complete Novel

(Francis Ford Coppola, 1983)

An epic melodrama for teenagers created with customary care, precision and passion by the masterful Zoetrope filmmaking family – shot by Burum, designed by Dean Tavoularis, cast by Janet Hirshenson – elevated even higher by this longer, fuller, rejigged cut, released shortly after Redux but well before the redemptive and similarly marvelous 2017 Encore of The Cotton Club. [George, why can’t you be more like your friend Francis! – LL.]

This version largely supplants father Carmine’s orchestral score in favour of an equally effective American Graffiti-style jukebox soundtrack, and other impactful changes include a patient new opening to introduce the Greasers and a restored courtroom denouement featuring a small, subtle, beautiful moment of cinematic elan.

Almost 40 years later, the headline remains the unbelievable cast: the Cruiser in only his third film, C. Thomas Howell, Ralph Macchio, the ‘Vez and Patrick Swayze in their sophomore efforts and Rob Lowe in his debut making experienced but still teenaged co-stars Matt Dillon and Diane Lane look like old hands. This octet spent the next ten years at the top of the business. I think no film in my lifetime has ever assembled an ensemble so unheralded yet whose individuals went on to such renown, not even Platoon.

Ishtar

(Elaine May, 1987)

Late ’80s Hollywood must just have been full to the brim with miserable buggers and snides I spose (David Puttnam is both) because there is nothing wrong at all with this clever-stupid Road To… farce except its production overruns and colossal budget ($115 mil adjusted), and why am I personally meant to care about those?

With the benefit of 30 years’ distance, the clearly deliberate insider takedown of the perfectly enjoyable Ishtar has all the hallmarks of industry adherents simply settling scores and unifying to bring a few big, powerful egos down a peg or two – ideology before content, just as we know it today. It’s a bloody shame that it was the rich talent of Elaine May that bore the terrible brunt.

So she shot an obscene amount of footage – not my problem. Everyone fell out with everyone else – doesn’t really show. It cost a fucking bomb – again, I don’t care. The desert denouement is botched, sure, attributable to May’s inexperience, but doesn’t fare so badly lined up against the current vogue for climax-less comedies, where forgetting to write a satisfying conclusion is industry standard. The rest of the flick is a charming tapestry of beautifully detailed Paul Williams songwriting, classic Charles Grodin scene-stealing and light geopolitical satire hung as backdrop to the winning Dustin Hoffman-Warren Beatty Ferrell-Reilly double-act. Simply put, Flight of the Conchords Go To Morocco.

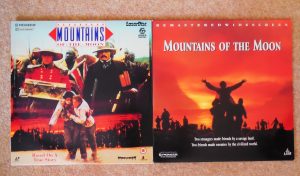

1492: Conquest of Paradise; Mountains of the Moon

(Ridley Scott, 1992; Bob Rafelson, 1990)

The hours of lockdown spent listening to glorious Ridley Scott commentaries while queuing for the post office stoked my enthusiasm for his characteristically bold Columbus epic. As ever with Ridley, you graciously nod through the weaker stretches safe in the knowledge that No 1, the environments and their photography will be stunning, and No 2, Scott and his team will deliver individual elements and sequences of incomparable eloquence.

There’s plenty to enjoy, not least taking in a lesser-seen example of Ridley’s devotion to filling the frame with airborne stuff: rain in Blade Runner, sand and grit in Black Hawk Down, snow in Gladiator and Kingdom of Heaven, fucking bubbles in Legend, and here, wind, in the form of, with marvelous thematic resonance, a boatload of flags.

Shot by Deakins, Rafelson’s excellent Mountains of the Moon, in which Patrick Bergin and Iain Glen go looking for the source of the Nile, hits many of the same beats as 1492, and, for that matter, as one of my favourite films of the last decade, James Gray’s The Lost City of Z.

I’ve begun to really enjoy the comfort of the formula to which these earnest exploration epics conform. There’s always an iconoclast hero, in enmity with the corruption of the Old World, initially in search of scientific glory in the undiscovered country but soon converted by his travels and evangelical about the deeper truths to be found among the natives. There’s always an initial sortie followed by a resolute return voyage; always a trusty lieutenant; always a hissable, suitably pantomime rich prick antagonist (in 1492, the ever-welcome Michael Wincott, and in Mountains, the ever-welcome Richard E. Grant); always a scene in a grand hall where our guy stands alone against the academy while the stuffed-shirt establishment bristle and bray.

And in Mountains of the Moon, you get all that, plus a bit where the King of Tanzania hands a pistol to a baby. Five stars!

Year of the Comet

(Peter Yates, 1992)

Studios so dedicated to reboots and remakes and resurrections of intellectual properties would do well to leave alone the sorta stuff that ain’t never gonna be improved upon and instead spend 80 mil taking another crack at something like this.

Year of the Comet does not succeed, but it comes close. Its execution as a knowing throwback to both the derring-do and the screwballs of the ’30s and ’40s is charming enough, and still holds promise today. Leads Tim Daly and Penelope Ann Miller are very enjoyable as the typically bickering chalk-and-cheese pairing – he’s the boorish rake, hyper-capable to the point of parody; she’s the spirited and determined novice leading the chase.

On release, the film’s MacGuffin – a colossal bottle of vintage wine – was ridiculed, suggesting as it does a screenwriter in William Goldman perhaps no longer capable of relating to his audience – but I enjoyed that idiosyncrasy, and I enjoyed, too, that it moved the plot from London to Scotland to a favourite stamping ground of mine, the Cote d’Azur.

The picture’s problems seem to be time and effort – despite the brisk traverse through some lovely locales, at its worst it feels rushed, and cramped, both in its physical spaces and in its editing. The caper’s low-stakes are matched by too modest an ambition when they’d instead be better served by an expanded cast and, critically, at least another 20 minutes on plot and character development, particularly for the wan supporting players.

Apparently Goldman discusses the project in Which Lie Did I Tell? – I really must pick up a copy. Let’s hope someone dusts off this screenplay and hands it to, I dunno, Ben Stiller, or David Lowery – talents like that could revisit this and really make it pop.

(One last thing)

Well, that’s cheered me up a bit. Good old Palin!

“It’s a Good Life”

by Luke Littleboy

Lockdown wasn’t all selfies in the garden and baking banana bread for ol’ Luke Littleboy (#stayhome #flattenthecurve #quarantineandchill). My wife and I had a baby due in July. So, instead of wondering when a vaccine might come to market, or if Latitude would still go on, or counting the days before our eager young Chancellor would emerge from the Treasury sleepless, disheveled and looking ten years older, waving a single crumpled twenty-note like Paul Hackett in After Hours to ask us all ever so nicely if please for the love of God you could leave the house now and spend money somewhere on anything… Instead of thinking on any of that, I started to think hard about what I wanted to accomplish in those precious weeks before D-Day.

Naturally, I cataloged all of my DVDs, again. I conducted an audit of every drawer, every disc case, every toilet cistern, and added them to a new spreadsheet, arranging them by director/filmmaker instead of a rather unhelpful A-Z system I’d been using previously. [Luke, rest easy in your abecedarian rectitude – this is unarguably the only rational way to file motion pictures. – FW]

This quickly identified some gaps in various filmographies, which I promptly started to fill. As we pointed out in our recent article on streaming vs physical media, it’s a buyer’s market for DVD right now. You can find most any DVD for pennies on eBay or similar, two to three quid including postage.

DVD is my favourite format. It’s cheap, it generally has extra content you wouldn’t find on a streaming platform, and they don’t look bad at all on a large HD TV so long as you’re running a half-decent Blu Ray player.

So, here’s three films I watched for the first time, by three of O.S.S.’s favourite filmmakers.

Burke & Hare

(John Landis, 2010)

I’ve watched a lot of Landis recently. And when I say a lot, I mean that this year I’ve watched every single picture he’s directed, in chronological order, except for The Stupids and Susan’s Plan, which I couldn’t get my hands on.

There’s a lot I could write here, about how The Blues Brothers is still one of the goddamned most blissfully anarchic things you could ever imbibe – second only to the climax of Landis’ own Animal House. About how Into the Night has the best David Bowie cameo ever, and that the young Jeff Goldblum and the even younger Michelle Pfeiffer are two crazy kids you definitely want to see get together. [What’d I tell you, eh? – FW]

But instead I want to simply point out that Burke & Hare, a film Landis made for the revamped, 21st century Ealing Studios, is a hidden gem of his career. And I picked it up at CEX for 50p. Every little helps, right, Chancellor?

Landis hadn’t made a feature in 12 years, so it instantly feels a little jarring to be watching him work with a contemporary cast. (Incidentally, he hasn’t made one since, either.) It’s a British production with a register of British comic talent, and supporting Simon Pegg, as William Burke, and Jessica Stevenson, as the wife of Burke’s accomplice Hare, there’s cameos for fellow Spaced alumini Bill Bailey, Reece Shearsmith and the inestimable Michael Smiley. (By the way, Spaced has been another one of my Lockdown rewatches – right now, All4, for free, people!)

Based on the Edinburgh Burke and Hare murders of 1828, we’re warned at the outset that the film we’re about to see will be taking some pretty big liberties with the truth. I honestly don’t know if Burke was infatuated with an ex-prostitute actress called Ginny who wanted to put on a production of Hamlet with an all-female cast. But I do know that Isla Fisher is charming, very funny and makes me want to give her all the money to make that production happen.

I also don’t know if these two murderers were so endearing and likable, but I do know that Andy Serkis and Simon Pegg have a decent chemistry and that they just seemed to be a couple of creative entrepreneurs to me. I was firmly rooting for them as Ronnie Corbett’s militia began to close in and a date with the hangman’s noose seemed inevitable.

It’s bawdy, modest, slightly low-key – at least compared to the wider John Landis oeuvre – but it’s good fun. And it makes me want another Landis picture soon.

The Second Civil War

(Joe Dante, 1997)

In our two-parter podcast on Joe Dante, we didn’t find much time for The Second Civil War. It flies under the radar compared to the Spielberg collaborations like Gremlins and Innerspace and the early, horror ones like Piranha and The Howling.

Maybe it’s because it was produced as a TV movie for HBO, or maybe it’s because it’s not a genre picture but an outright comedy, and a satire at that. In any case, The Second Civil War is Dante at his most biting and subversive. Told through the eyes of a myriad of TV reporters, media execs, politicians and press secretaries, it imagines a hypothetical constitutional crisis – Pakistani war orphans arrive in the US seeking asylum, the xenophobic Governor of Idaho breaks from the federal government to close his state’s borders, and suddenly the news media is licking its lips at the prospect of ratings-friendly diplomatic disarray.

As further people are displaced, the situation escalates. In this near future, the Mayor of Los Angeles is Hispanic and only speaks Spanish, and Alabama has a congressman from India. Politicians begin to point-score by supporting policies along ethnic lines. The Idaho National Guard clash with the United States military. A charity for war orphans deliberately leaves their charges in vulnerable positions, the better to tug at the public’s heart strings.

It’s a chilling look at the arguments we can expect when climate change finally uproots enough people to really affect us in the West and primal feelings of regionalism kick in. And Civil War‘s late ’90s presentation of the eroding integrity of the media functions today as prediction. We see a meeting in a newsroom where an exec is bartering with news editors about what international calamity should or shouldn’t be covered. “Use the Rwandan massacre”, he concludes, “there are no Rwandan advertisers.” And when a talking head blithely mentions a ‘second civil war’ during an interview, someone in the newsroom is immediately hip to the branding opportunity (“Get me graphics!”).

But it is funny. I promise. Beau Bridges is pitch perfect as the bumbling and bigoted Idaho Governor Jim Farley, blind to his love of Mexican food and the fact his own mistress is an immigrant. His cluelessness is well juxtaposed with his clued-up press secretary, played by Kevin Dunn. Phil Hartman’s moronic, poll-obsessed Commander in Chief isn’t remotely presidential, and his speechwriters make up fictional quotes from Eisenhower to lend him gravitas on TV, foreshadowing the fake news of the last five years.

The project also serves as an expensive casting call for Small Soldiers which Dante made for Dreamworks the following year – by my count they share seven cast members, including, of course, Dante stalwart Dick Miller.

It’s not Dante’s best but it is his own favourite. And you can see why. For me, it’s nudging my top three Dantes – almost as good as The ‘burbs and Matinee but not quite eclipsing the sheer lunacy of Gremlins 2: The New Batch.

Oh, and unfortunately this wasn’t a cheap DVD – I had to import it from Europe, and I can’t take the Spanish subtitles off. Although in the context of the subject matter of the film, that actually seems rather fitting.

She’s Having a Baby

(John Hughes, 1988)

From the opening titles, with a very ‘80s-sounding “It’s All in the Game” by Carmel playing over the Paramount peak, you know you’re in for a treat. Sure, lots of films open with a tune before you’ve even seen the studio logos. But did anyone else do it quite like John Hughes? You just know he’s been crate-digging in the den for 20 minutes, returning to the hi-fi with a smile and a 12-inch, “Hey! Have I got a story for you.”

We open at a wedding. Oldsters gossiping about the bride and groom. Kevin Bacon’s Jack is about to marry Kristy (Elizabeth McGoverrn). Kevin, sat in a car with pal Alec Baldwin, has the jitters. He asks his friend if he thinks he’ll be happy in life. “Yeah, you’ll be happy. You just won’t know it, that’s all”.

Wow. What a line! I was expecting it – I know the scene. They even used it in Hughes’ Oscar tribute. But in this context it really hit home. We’ve had a lot of sleepless nights since our baby was born, and three years of marriage has already taken us from London to Bournemouth to East Anglia [Occasionally in the same day! – FW] Sometimes it’s worth keeping in mind that life is wonderful – even if there’s lots of living getting in the way of it.

We see Jack and Kristy struggle as a young couple, and arguments over in-laws, career choices and furniture feel familiar. Writer-director Hughes toils to temper the close-to the-bone domestic turmoil with quick fantasy cutaways. Bacon’s office set closes in on him as the grind of the job begins to bite. And the men of the suburbs erupt into a choreographed musical number when mowing their lawns.

The prison of domesticity comes into sharp focus when bad boy bachelor Baldwin visits their suburban home and sows seeds of discontent. Kevin starts thinking of escape, to get him writing and out of his unfulfilling job. “I measure my life in degrees of happiness” his boss tells him. “I’m supporting my family in a way that makes me happy. I’ve got a nice house, a really nice car, and once a year I write an ad that I’m proud of.” When Bacon asks if that’s what he really wants, his boss says “No, that’s what I take. You never get what you want.”

Jack asks himself – is that all there is? Kristy begins to question what she really wants from life, too – and soon Jack finds himself going along with a plan to have a baby, despite his reservations, anxiety and fantasy of escape.

Luckily – thankfully – I was never in this position myself. But the tearful ending was certainly something I could relate to. There are few things that matter in life more than the people around you who care about you. Somewhere amongst the mundane and the moribund existence of every day is an exceptional ecstasy if you allow yourself to be open to it. I think all of Hughes’ films are about that on some level. And I couldn’t have watched She’s Having a Baby at a better time in my life.

(One last thing)

Credits cameo cavalcade!

OSS20-0313/0816FWLL104 – From the Files of O.S.S. – 28 Weeks Later: The O.S.S. Guide to What We’ve Been Watching in Lockdown