OSS17-0913/1001FW102-2 – A Guide to the Films of Shane Black Part 2

In 1987, Shane Black broke Hollywood in three ways.

Lethal Weapon, his second screenplay, had been bought for $250,000, had been shot by Richard Donner and Joel Silver for $15 million, on release brought in an unexpected $120 million. John McTiernan’s Predator, in which Black accepted a prosaic gig as script doctor to secure from producer Silver a coveted supporting role, was a similar story – budget of 15 mil, box office north of 90. Both pictures stand as classics of their era, while the former is arguably both originator and apogee of its genre. Taking bronze, affectionate horror pastiche The Monster Squad, Black’s collaboration with friend Fred Dekker, which though a commercial damp squib was a fast cult favourite.

He was 26.

Young, gifted and Black. And fucking rich.

What immediately followed was a three-pronged education in Tinseltown disaffection, a triptych of varied frustrations for the writer in Hollywood.

Obstruction 1: Tasked with taking on the inevitable Lethal Weapon sequel, Black spent half a year penning his opus, Play Dirty. When that work was rejected, he walked away from the project entirely, even had to be talked out of returning his fee. On release, Lethal Weapon 2 was a smash, but it comprised few of his ideas and little of his intent.

Obstruction 2: The scorching screenplay for The Last Boy Scout sold for an unprecedented $1.75 million. Twelve months later a notoriously punishing production had robbed that remuneration of any radiance. Black had been paid, but he had been made to pay.

Obstruction 3: art ate its own arse as a parody of Shane Black wound up rewritten by Shane Black to reach screens as Last Action Hero, an ambitious, lively action satire torpedoed by overexposure and greeted with delighted mockery. The Blacklash had begun.

By 1993, Hollywood had broken Shane Black in three ways.

Seven years. Six screenplays. Five films. Here’s something Shane Black learned: Hollywood posture, patronise, praise and, particularly, pay, persistently preposterously; but regardless of budget or box office or even the money he was making, Hollywood not transpose from script to screen what Shane Black actually wrote.

“Nobody likes you. Everybody hates you. You’re gonna lose. Smile, you fuck.”

– Joe Hallenbeck, The Last Boy Scout

This is Part 2 of our guide to the films of Shane Black.

Lethal Weapon 2 (Richard Donner, 1989)

written with Warren Murphy, re-written by Jeffrey Boam (and again by Robert Mark Kamen), produced by Joel Silver

Does the title begin with an L?

Unequivocally-er.

Is it set at Christmas?

Nope. Black’s original draft wasn’t set at Christmas either – but that and the “stilt house” set piece seem to be the only elements left unchanged.

Mismatched partners?

“We’re back, we’re bad, he’s black, I’m mad.”

Scene-stealing henchman?

Mark Rolston’s Hans, who loses a huge haul of Krugerrands when driving at high speed trying to shake off a typically tenacious Riggs. When asked to account for dropping a million dollars’ worth of gold, he offers only, “I’m sorry, Mr. Rudd. It happens.” It’s a bold approach. He’s certainly owning that mistake. But unsurprisingly, Rudd’s like, “Drake, you are LEAVING!”

Brilliant second-baddie?

Pieter Vorstedt (Derrick O’Connor, looking and sounding like an own brand Daniel Craig in Munich). Strengths: bit of an all-rounder – victim interrogation, victim murder, victim disposal. Also, knows capoeira, or at least stopped to watch a capoeira class in the park three weeks in a row and reckons he has it down. Weaknesses: racial equality legislation, shipping containers.

(In less charitable terms, Vorstedt is vather a vetreadt of Mr Joshua. And, all kidding aside, Hans’ demise is pathetically underwritten – it’s difficult to see Black writing a henchman kill so carelessly.)

And who’s actually the baddie?

Joss Ackland as hissable racialist Arjen (pronounced by Riggs as “Aryan”) Rudd, a character forever synonymous with the words “DIPLOMATIC”, “IMMUNITY” and “DIPLOMATIC IMMUNITY.” Revealed to retain responsibility for events before the first movie too, so we’d say he’s the dickhead now.

Post-traumatic Shane disorder?

Riggs finally gets closure on his back story, so he won’t be popping pistols in his mouth anymore. Unfortunately, this means that by Lethal Weapon 3, Riggs has become the kind of wacky self-parody that subdues a pitbull by falling to his hands and knees and panting like a dog, at which point the people contemplating suicide are in the audience.

Fallen angel?

A tragic ingenue, as Riggs is ready to take a chance again with Rika, a South African secretary in the incongruous form of Patsy Kensit. There she is eyeing up Riggs’ Letterman jacket, which I’ve forever found dashing and iconic. Not having a go, but three decades later it’s difficult to remember who, what or why a Patsy Kensit is. How to explain her to the youth? “An ‘80s/‘90s Estella Warren who fucked lead singers but drew the line at Mick Jones”?

Trash-talking teen?

Basically Patsy, again (she was like 19 during filming). Now she’s wearing Riggs’ Letterman jacket, while drinking a beer!

I’ve always had a problem with these scenes. Look… given the lack of drinking experience implied by her youth, I’m very surprised that he’s allowed her anywhere near that jacket with a brew. Even as a character beat to establish his new willingness to give of himself and to open his heart and to trust again, no, it doesn’t ring true. Yes, he’s a maverick, but, for me, the risk Riggs is taking there is not only unacceptable, it’s unbelievable.

Kidnap?

The baddies prove their shit credentials by swiping Riggs’ Letterman jacket and chucking it in the ocean (seen here with Patsy still in it) which, I’m sorry to say, rather amplifies my earlier point. Riggs arrives just in time – but while the woollen body of the jacket should be okay, brackish water has the potential to wreak havoc on those leather sleeves. First, he’ll need to use a cloth dampened with clean water to remove the salt residue and avoid unsightly tidemarks. Then, air dry (no heat) on a hanger at room temperature, a day-long process, after which he’ll want to apply a decent leather conditioner that doesn’t contain wax or silicone, which would dry the leather out. And, all of that will have to work concurrently and in tandem with a bit of TLC for the woolen parts. But, with that level of aftercare, the piece should make a decent recovery – though Rog may complain of the smell!

Riggs isn’t seen wearing the jacket in either Lethal Weapon 3 or Lethal Weapon 4, but I suggest that’s attributable to a revised approach to its wearing, a more occasional usage in order to better preserve the item, rather than disuse or disposal. I’ve read the fan arguments that Riggs binned it off entirely but for me, pardon the pun, they don’t hold water. Omission hardly counts as proof and there’s no canon evidence in either sequel to support those speculative theories; indeed, I’ve seen early drafts of 4 that made specific reference to the jacket, and at one stage it was considered to return for the TV series.

(Patsy was a write-off.)

Blackmail?

Who needs Blackmail when you’ve got DIPLOMATIC IMMUNITY.

Domestic bliss?

In classic Shane style, family and all its accoutrements are under threat, physically and ideologically. A running gag involves the gradual destruction of Trish Murtaugh’s new station wagon, seen here taking a panel beating from an airborne crapper; Murtaugh shows off a two-car garage and hobby room, which he later vehemently defends with carpentry tools (“Nailed ‘em both!”); and in the picture’s most memorable set piece, Rudd’s racialist rotters rig a bomb to Rog’s bog.

Fucking with a man’s lav. That’s… that’s unforgivable. No way you live, Joss Ackland. No way.

Elsewhere, daughter Rianne’s big acting break turns out to be a commercial for condoms. Despite the tagline – “Because caring means all the protection you can get” – sounding like Roger’s personal credo toward his own brood, his solemn reaction – “Trish… Take the kids upstairs…” – suggests he was just zapped with a premonition of a Mel Gibson traffic stop.

They’ve read all the books and seen all the movies

As in the previous installment, Murtaugh’s TV is playing some festive fare – this time, somewhat awkwardly, it’s Mary Ellen Trainor’s appearance in a very early episode of Donner and Silver’s Tales from the Crypt.

None more Black

The difference between a Lethal Weapon film written by Shane Black and a Lethal Weapon film written without Shane Black, is the difference between a Banksy stencil on the wall of a north London Poundland and a Banksy stencil on the wall of a north London Poundland removed brick-by-brick and transported to Switzerland for auction in Miami.

Residual Rog-and-Riggsisms remain but where Martin would quote Three Stooges before blowing away three drug dealers and begging a fourth to shoot him, he now jokes, “Eeenie, meenie, miny… Hey Moe!” as he blasts open an office aquarium then wanders away gaily to the lick of Slowhand’s Strat while wet-socked bad guys flap over tropical fish.

Written by Black, Riggs was reckless because he’d lost the will to live. Written by Hollywood, Riggs is reckless because that’s how an action comedy makes $200 million.

..but…

..this is Dick Donner, directing peak Gibson and Glover, with a screenplay from the writer of Innerspace and Last Crusade, scored by Kamen and Clapton, and foregrounding half a dozen baddies equipped with the world’s most evil accent.

DIPLOMATIC! IMMUNITY!

It’s not art, but it’s bloody good fun.

The Last Boy Scout (Tony Scott, 1991)

written by Shane, story credit for Greg Hicks, produced by Joel Silver

Shane Black’s final draft for The Last Boy Scout is superb. The finished film is a minor gem. Everything in between is remembered with the same fondness as pissing out a kidney stone.

The shoot, a daily dick-waggling between a toxic troika of alpha pricks, was fucking miserable. Willis hated Wayans. Scott despised Silver. No one was satisfied with Black’s screenplay. And after wrap, a veritable death march of an edit.

Post-production burned through cutters like Kevin Shields buried studio engineers. At least seven editors struggled to render coherence from 1.6 million feet of beautiful Tony Scott coverage. Mark Helfrich commented, “There was more footage shot for The Last Boy Scout than on any film I had ever worked on.” Mark Goldblatt, acclaimed from pictures with James Cameron and Paul Verhoeven, didn’t comment anything, because 25 years later he still utterly refuses to discuss any aspect of the process, ever.

Hilariously, what eventually wound up in cinemas that Christmas didn’t even have the verve to bomb properly, The Last Boy Scout’s underperformance already cast unexceptional in the new context of Willis and Silver’s other big picture that year, summer flopbuster Hudson Hawk, which comfortably lost 50 million. (Tell you what, though, the Ocean Software tie-in is a riot!)

Does the title begin with an L?

It does.

Is it set at Christmas?

Of course.

Kidnap?

Word.

Blackmail?

Affirmatron.

Mismatched partners?

Black guy, white guy

Joe Hallenbeck: used-up white PI and disgraced Secret Service agent with a developing alcohol dependency and outdated principles of valour.

Jimmy Dix: used-up black ex-football player and disgraced QB1 with an addiction to painkillers and six-hundred-and-fifty-dollar leather pants.

Post-traumatic Shane disorder?

Hallenbeck crawled into a bottle after punching out the politician he was paid to protect proved professionally imprudent. Hot young superstar Dix had a pregnant wife killed in a road traffic accident and a newborn son that lived 17 minutes in an incubator; after that he sorta lost his appetite for sporting endeavour. “I threw for three hundred yards that day while my wife and kid were dying. I played the game of my life.” We’re rather a long way from The Monster Squad.

Fallen angel?

Halle Berry as Dix’s stripper girlfriend, whose murder kicks off the plot.

Trash-talking teen?

Halloween scream queen Danielle Harris, superbly prickly as Hallenbeck’s smartmouth 13-year-old daughter, Darian. Noticing Dix’s barbershop shave, “The hell’s that number on the back of your head? Is that like a license plate in case somebody tries to steal it?”

Domestic bliss?

Joe is introduced disheveled and sleeping in his car. Neighbourhood children giggle as they wave roadkill over his face. His morning mantra: “Nobody likes you. Everybody hates you. You’re gonna lose. Smile, you fuck.” About an hour from now he’ll be asking his libidinous best friend at gunpoint, “How was she? On your ‘finger scale’, how was my wife?” His predicament, as summed up by Jimmy Dix: “You’re trying to save the life of the man who ruined your career, and avenge the death of the guy that fucked your wife.”

Scene-stealing henchman?

Numerous memorable bit parts from familiar faces, including Jack Kehler’s brief turn as a verbose enforcer and Kim Coates playing himself.

Brilliant second-baddie?

Eighties cameo king Taylor Negron deploys his trademark sarcastic schtick in a delightfully mannered performance as sociopath Milo. Congrats to casting – Negron is not the obvious choice, but his proto-Malkovich delivery wrings camp menace from every smiling civility. In the aftermath of the film’s most famous kill, consider the relaxed confidence he conveys simply by inserting the qualifier “awful.”

And who’s actually the baddie?

Noble Winningham as LA Stallions owner Shelly Marcone.

Convoluted conspiracy?

His plot is an interplay of bribery, extortion and assassinations between two great institutions, the NFL and the Senate. Says Shane, “Football is the perfect medium because it combines the spirit of the American hero with the spirit of American greed.”

None more Black

McCoskey: Good morning gentlemen, is there a problem?

Milo: Yes, officer, as a matter of fact there is a problem, apparently there are too many bullets in this gun. (BANG)

They’ve read all the books and seen all the movies I

Milo: Can we do a formal introduction here?

Hallenbeck: Who gives a fuck? You’re the bad guy, right?

Milo: I am the bad guy.

Hallenbeck: And I’m supposed to be trembling with fear, something like that?

Milo: Something like that.

Hallenbeck: Fine. I’ll start trembling in a minute.

They’ve read all the books and seen all the movies II

Hallenbeck: Since it’s the ’90s, you don’t just smack a guy in the face. You say something cool first.

Jimmy Dix: Like, “I’ll be back.”

Hallenbeck: Only better than that. Hit him with a surfboard…

Jimmy Dix: “Surf’s up!”

Hallenbeck: Something like that.

(a nod to a gag in Lethal Weapon 2 that Shane didn’t write!)

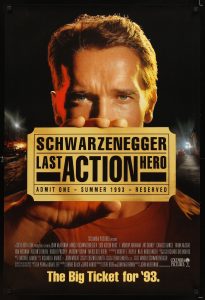

Last Action Hero (John McTiernan, 1993)

written by Adam Leff and Zak Penn, re-written by Shane and David Arnott, doctored by William Goldman(!)

I remember the release of Last Action Hero. “The big ticket for ’93!” The long campaign of posters and print ads. The trailer – Arnie in Shakespeare on semi-auto, Arnie on the balcony with the Desert Eagle, a British bloke with a shades and a pistol and a mental eye. It looked, approximately, like the best movie ever. But I heard the excoriating press and accepted, it might be the worst movie ever.

Luke will remember its release because, decisively, it was deliberately gazumped by Jurassic Park. Amid gossip of disastrous test screenings, a predatory Universal smelled Sony blood and brought their blockbuster forward a few weeks to open seven days before the competition. Sony executive Mark Canton decided not to blink first. No prizes for guessing which one was the goat.

Last Action Hero got blown away. It was undone by the revised release dates, a maelstrom of manic marketing, a smug Sony Studios obsessed with synergy, and an always inadvisable alliance of hubris and hype, headed by Canton. Tie-ins reached saturation for both movies, and both boasted a publicity price tag comparable to their actual production budget. But as ever, “Teflon” Steve escaped unscathed (see also: The Twilight Zone, The Flintstones, Transformers) as critics instead sharpened knives for Last Action Hero’s overblown proliferation – in toy shops and burger bars, sure sure, but also at motor speedways, as a four-storey fuck-ugly inflatable, and on the side of a Nasa rocket (which then failed to launch).

But what about the film? Eighteen months later I watched it on video and I don’t know why but I wanted to think it was crap. P’raps I thought that as a film fan I ought to concur with critical consensus. It had been vilified in pop culture; I heard the writer was a jerk; I didn’t like the look of that kid; it wasn’t Jurassic Park. I wanted to watch it and know it was stupid.

Was anything actually wrong with it? I didn’t like the kid, I think out of jealousy, but his mum was Big’s mum. Hamlet with an Uzi was as riotous as in the trailers. Charles Dance shot somebody and he did it on purpose. Arnie fell off a building. The Ripper was scary, and Death was even scarier (in fact, Ian McKellen’s Death was the second most frightening thing I’d ever seen and I literally couldn’t sleep.)

It wasn’t The Untouchables. It wasn’t Die Hard. I didn’t know who Art Carney is. But it had cameos and references and hyperbole that made a pre-teen film fan laugh and cheer and feel a part of something. In context, it’s The Monster Squad for ’80s action. Luke, we need to watch this together!

Does the title begin with an L?

Certainly.

Is it set at Christmas?

No, and yet still the first line is a knowing, “This is one hell of a way to spend Christmas.” It’s not even set in Los Angeles, at least not really. Reality is a grimy New York City, a few blocks from 90th Precinct. When we step into the movies, it’s sun-kissed La La Land all the way. “Where are the ordinary, everyday women? They don’t exist because this is a movie!” / “No, this is California.”

Mismatched partners?

Real world teenage movie buff, fake world action movie cop

But Black and Arnott also parody the cliche: a desk sergeant reads morning roll call – “Oiler! You team up with Waterman. Krause, you team up with the rabbi”, then turning to address a cameoing Colleen Camp, “Ratcliff, you’re on duty with the cat.” The latter is a three-foot tall cartoon tabby dressed like Bogart with the voice of Danny De Vito (“That cat is one of my best men!”)

Trash-talking teen?

Lead Danny Madigan (Austin O’Brien), borderline bearable.

Domestic bliss?

In the real world, the family unit is Danny, his mother and the mounting bills in their cramped New York apartment.

In Hollyweird, returning to a bare condo (with a swiftly-dispatched ninja in the closet), Jack concedes “the job” is all he has: “I pay a cashier to call me at work, so the guys think I have a life. My ex-wife is happily remarried. She never calls. And Whitney? On prom night she stays home to field strip an AK-47. She’ll die a young maid. I’m going to buy it soon, too.”

Post-traumatic Shane disorder?

Since the death of his father, Danny’s taken solace in cinema, in particular bulletproof action hero Jack Slater. Slater himself is empty – Black takes us behind the bravado and finds “nothing but pain.” Laugh if you like, but Arnie tried acting on this one and the subtleties show. It’s poignant that he best conveys angst when playing a hollow movie superman realising his own artifice.

Scene-stealing henchman?

The Ripper, a hysterical rendering of an axe-wielding grotesque in butcher’s chainmail and a sou’wester, typically underplayed by the wonderful Tom Noonan, who, because it’s definitely that kind of film, also cameos as himself. So, when a red carpet mic jockey at the premiere of the new Jack Slater mistakes the movie bad guy, now magically transported to the real world, for Noonan-gone-method, we get the following exchange:

Chris Connelly: It’s the Ripper from Jack Slater III. ‘Scary’! Let’s axe him some questions! Rip! Rip, what brings you here tonight?

Ripper: I, uh… I thought I might kill someone.

Chris Connelly: Well, you should start with your designer!

Brilliant second-baddie?

Supremely self-aware assassin Benedict, enjoying himself as much as Charles Dance, the actor playing him, who gives a joyful performance. Evil accessories: Denholm-Elliott-in-British-Honduras-style white linen suit; tortoiseshell Wayfarers; revolver with a 12-inch barrel; variety of fake-eyeballs; easy rapport with us, the audience – “If God was a villain… he’d be me.”

James Kennedy’s favourite line: “I snap my fingers again and some time tomorrow, you emerge from several canine rector.”

And who’s actually the baddie?

Ostensibly, Anthony Quinn’s clueless “spaghetti-slurping cretin” Tony Vivaldi, barely in it.

They’ve read all the books and seen all the movies

As I thumb through Last Action Hero in my mind, I can’t recall a single serious issue. The entire picture is a satirical, superficial self-aware parodic delight of having its banquet and eating it, too, with the appropriate RDA of Black pathos (I call it “Blathos”) to reel us in. That audiences were unreceptive, and yet responded to New Nightmare the same year and lapped up Scream three years later, is likely attributable not to any issues of quality but to the farrago of its release and the strength of its competition, both at the box office, in the form of Jurassic Park, and within the incredible pedigree of the careers of its director, its lead and its writer.

None more Black I

Jack Slater: Sir, are you a henchman?

Benedict: No, I only go as far as “lackey”.

None more Black II

Jack Slater: Kid! Who does the doctor treat?

Danny Madigan: Patients?

Jack Slater: Look at the elbow of my jacket. What is it doing?

Danny Madigan: Wearing thin?

Jack Slater: Bingo!

Further reading: We go back to the 80s with Monster Squad and Lethal Weapon, in part one of our Spotter’s Guide to Shane Black

Further listening: We discuss what’s Black, Blacker and Blackest in our tribute to Shane Black on this podcast.