In the third and final part of our year in review, Fletcher Walton and Joe Espiner look in greater depth at five of the features that got us to the pictures in 2021. And in the week of the 50th anniversary of its UK release, fresh from a cinema viewing back in September, we reconsider a single fascinating scene from A Clockwork Orange.

Last Night in Soho

(Edgar Wright)

Across five films this century, Edgar Wright has proven himself the best action director English language cinema has produced in 30 years. But his ever-developing technical elan has always been complimented by strong work as a writer.

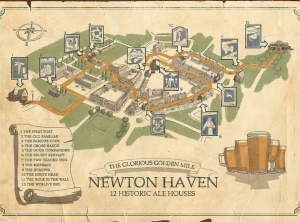

Probably the result of a half-decade spent crafting hyperverbal alt-situation and sketch comedy like Asylum, Is It Bill Bailey? and, of course, Spaced, Edgar Wright’s cinematic collaborations with Simon Pegg are characterised by their dizzying dedication to detail and dialogue.

Every utterance is a portent (“If you wanna be a big cop in a small town, fuck off up the model village!”); or it’s a call back (“Is it a door? Because it doesn’t have a lintel”); or it elegantly reflects character (“We split up with Liz tonight”), or plot (“And the front door is open again!”), or both (“Next time I see him, he’s dead.”). On the odd occasion when a line of their dialogue doesn’t do any of that, they might have chosen to give themselves a break and only be funny.

Wright wrote the similarly dexterous Scott Pilgrim vs the World with Michael Bacall and then Baby Driver on his own, to no discernible deficit in the depth of dialogue. His latest screenplay, Last Night in Soho penned with Krysty Wilson-Cairns, is a psychological horror in the ’60s/’70s European tradition that offers a fine concept – a country mouse in the present retreats into dreams of an idealised past whose sordid realities begin to shape her future.

Wright’s visual tailoring is typically inventive, as early scenes joyfully weave these twin timelines around one another, with all sorts of in-camera tricks and soundtrack fun. The horror hi-jinks are fashioned around a thematic fabric of sexism and trauma, and the film conducts a singularly cinematic conversation between now and then, between a naïve youth confronting awful truth.

Then after about an hour, it simply stops being at all interesting.

Last Night in Soho suffers from being shockingly shorn of Wright’s usual sizzling wordplay but more surprisingly, its wan, artless dialogue is only the most substantial, bloodied swatch of a patchwork of errors: in Steven Price’s score, which feels too parochial for the viscera of its genre; in character, where the lead is set up to learn and change but in execution doesn’t do either; and, particularly, in plotting. The stitching unravels most completely in an embarrassing vomit of third act exposition that loudly announces yards of character and plot rather than doing what cinema is meant to do and showing it to us.

I was reminded of the patience and panache with which Wright & Pegg crafted Hot Fuzz’s byzantine land-grab conspiracy, which in practice is deployed only as a watertight red herring. Last Night in Soho stands smaller still in comparison. For all of Wright’s customary and commendable attention to visual and aural detail, I was ultimately left dreadfully disappointed by the indolence of the writing. FW

Jungle Cruise

(Jaume Collet-Serra)

Once again Disney eats itself, returning to the theme park dry dock for ideas to launch a fresh franchise fleet of rollicking, old-fashioned action-adventures, hoping to replicate the boffo box office of Pirates of the Caribbean rather than the underwhelming returns of The Haunted Mansion (or the poison of The Country Bears). All the Pirates elements are on deck – the idiosyncratic boat captain, the spirited English rose, the undead baddies, even the bit-part Brits (Britparts?) familiar from television (Andy Nyman, come aboard!) – and with a production budget identical to Gore Verbinski’s 2003 smash, Jungle Cruise is clearly intended as this decade’s sequel-spawning flagship.

The pedigree is halfway promising. Director Jaume Collet-Serra is among the busiest B-helmers this century. His filmography shows a patient progression through the ranks, from low- and mid-budget horror up to mid-budget action as Liam Neeson’s preferred confederate, and now, with Jungle Cruise and with star Dwayne Johnson’s next project, DC adaptation Black Adam, two big bites at the blockbuster cherry.

Currently steering at least six franchises(!), Journey and Jumanji veteran Johnson is a perfect fit for light-hearted effects-driven action-adventure, as is Emily Blunt – both are adept, affable A-list comedians who work well with others. There’s also a writing credit for Requa & Ficarra, and while we’d anticipate their work here will be more Cats & Dogs and Bad News Bears than Bad Santa and I Love You Phillip Morris, that’s reason to remain optimistic.

Optimistic, without going overboard – it is, clearly, too much to ask contemporary filmmakers to shoot for Raiders of the Lost Ark; indeed, it’s too much even to ask that they shoot for Raiders and hit The Mummy, because 20 years on, Stephen Sommers’ enjoyable Indy clone feels like an unreachable highwater mark in itself. But, yes, Jungle Cruise is fine. Good performances all round, decent character support from Paul Giamatti and Jesse Plemons, the always welcome Edgar Ramirez giving good baddie, and a genuinely surprising midway twist. Almost 19 years ago, the both of us were completely outflanked by the gargantuan success that came out of the original Pirates, so who are we to prognosticate what (sea) legs this one will have.

One aspect rankled. In a superficial display of inclusion, Jack Whitehall’s snobby fop McGregor Houghton may – to use the kind of coded language employed by the film itself – parade in Carnival. However, his “coming out” scene is so coy and cack-handed that all we learn is that he’s broken off three marital engagements because his “interests happily lie…elsewhere”. But by leaving his character as a nudge-wink ‘confirmed bachelor’, the filmmakers are in effect letting the viewer take a wild guess at just what these other romantic interests might be. Is McGregor gay? Perhaps he’s a voyeur? Could he be a necrophile? Maybe, like Disney executives, he’s brought to sexual frenzy by 200-million-dollar acts of competent corporate synergy? Reader, it’s all very distracting. JE & FW

Dune

(David Lynch)

Is there anyone even vaguely interested in sci-fi or cinema who doesn’t have a soundbite to wheel out for Lynch’s Dune? Most likely along the lines of, “Over-reaching… interesting moments… studio bosses… imagine what Jodorowsky’s would’ve done with it, eh?”

All the cliches are true: there IS too much plot for one film; Sting IS pointless but looks great in his knick-knocks; viewers DO need a snoot full of Melange to help them make it to the end credits.

But, my God, the moments where it does work are jaw-dropping. Almost all involve House Harkonnen and their home planet of Giedi Prime – these scenes are fully realised, they have great art design, they are completely bonkers-scary. The score (famously by Toto) is fantastic, and the effects hold up – surprisingly, mostly still superior to the 30 years of CGI-heavy SFX work that followed.

And throughout the picture, indeed from that masterful opening narration, Lynch the expert filmmaker avails himself of all sorts of interesting cinematic techniques attempting to wring a coherent two-hour movie from Herbert’s solemn tome. Dune is a misfire, but one that still hits parts that other films cannot.

Dune

(Denis Villeneuve)

The remake – and it is a remake, arguably scene-for-scene – is a tricky one. Grown-up blockbusters in the mould of Nolan or Scott are far too rare these days, so it’s great to see a big budget release not aimed exclusively at teenagers or the mentally deficient. But compared with Lynch’s dog’s dinner feast, this is thin gruel. That might be enough for wan half-man-half-Twiglet Timothee Chalamet, but not for the rest of us hungry customers.

At many points this struggles under the weight of its own seriousness. Where are the big battles? Where are the jaw-dropping Harkonnen scenes that we got with Lynch? Where are the sly winks to the audience in concession that, yes, this slender tale is fundamentally Flash Gordon for poseurs? Where’s the FUN? Maybe that’s been held back for Part II, which I will dutifully go to see – well done, Warner, another tenner bilked – in the hope that after this serviceable but meandering prelude, the sequel will deliver something worth watching in [checks] two years’ time? Oh, come on! JE

The Green Knight

(David Lowery)

The first lesson I learned from Lowery’s latest is that I can trust him as a filmmaker as long as he can trust me as an audience. The Green Knight is at once inscrutable and perfectly comprehensible because at every step, Lowery showed me all that I required to understand his film as long as I sought to participate. It’s edifying and refreshing to be treated as an adult by an American director.

So, while it’s true: that we are at Camelot, that Dev Patel is Gawain, that his liege Sean Harris is King Arthur, that his fuck-off sword is Excalibur, and that none of that is necessarily explained more than once, it’s also true that those superficial details are not integral to our comprehension of what matters in this story.

With a fatalism and sparse eloquence that recalls Cormac McCarthy, Lowery uses cinema thriftily to make clear enough what we need to understand: Dev is a callow, feckless squire eager to impress at the court of his uncle, the ailing king; an unbidden stranger, seemingly conjured by Dev’s own mother, arrives to suggest a contest, instigating an opportunity for mercy that Dev brashly declines; 12 months on, after fucking about for a year, Dev has a week to find within himself the chivalric responsibility to meet that stranger in a rematch, or try to weasel out of it.

This entails an hour-and-a-half in the endlessly engaging company of Dev’s brow and beard and blue-black locks, plodding about splendidly-shot Gilliam-esque landscapes enjoying character-building interludes with those landscapes’ splendidly-realised Gilliam-esque denizens, including: a typically shifty Barry Keoghan…

..Erin Kellyman from Solo, some giants, a nice foxy, and Joel Edgerton and his wife, Alicia Vikander, who’s already turned up as earlier as Dev’s lowborn girlfriend. After all that, which invariably looks and sounds amazing, Dev must decide whether or not to face his fate.

It’s edifying to be treated as an adult but it’s also challenging, and watching The Green Knight I was working, enthusiastically but unmistakably, above my skill level. Lowery’s ideas often coalesced for me only hours or even days later. Nevertheless, watching in the cinema, the film and its themes imprinted on me at a more instinctual level, at an experiential level – to appropriate from Martin Scorsese, discussing the pan to the empty hallway in Taxi Driver: “If I could really put it in words, I wouldn’t have had to put it on film.” In this way, I was reminded not just of Lowery’s own magnificent A Ghost Story but also Nicolas Winding Refn’s Valhalla Rising, in which nothing is explained but everything is understood – or, perhaps more accurately, felt.

The Green Knight is without doubt the best new film I saw all year. It is deliberate in its filmmaking, and its relative difficulties make it all the more rewarding. It is audacious in its discussion of bravery and honour, fallibility and invulnerability, particularly in the context of what the cultural mainstream is doing and saying in 2021. Disconcerting moustache notwithstanding, David Lowery is – fuck it – the most exciting American filmmaker to emerge in the last 15 years, and I am very thankful to both A24 for the indies and the evil ol’ House of Mouse for the family films. Roll on, Peter Pan & Wendy. FW

A Clockwork Orange

(Stanley Kubrick)

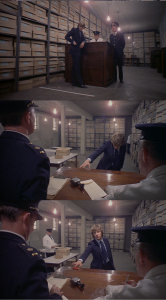

As discussed previously, watching a familiar film at the pictures for the first time is absolutely the best way to reconnect with the primacy of cinema exhibition over any other means of viewing. The removal of distractions and the undeniability of that colossal screen focuses the mind and demands an engagement with the text that will reveal new depth and pose new questions no matter how many times you’ve watched the fucker on video. This exercise is never more fulfilling, and the questions emerging never more precise, than when you take your seat to watch a film by Stanley Kubrick. And so, back in September, I left A Clockwork Orange pondering a sequence to which I’d never before paid any attention: what’s going on with that prison induction scene?

Kubrick is not a realist director and A Clockwork Orange is not a forensic treatise on penal society, it is not Audiard’s A Prophet. If the film spends five minutes depicting the minutiae of Alex’s arrival at prison (twice as long as Landis memorably spent on the obverse) culminating in a right good look up his arse, it’s because it serves the filmmaker’s central themes to do so. What could Stanley be telling us?

The scene shows a new environment in which Alex is quickly stripped of his identity and completely subordinated to restrictive, unyielding order and process, implemented by militaristic martinet Chief Guard Barnes. But surprisingly, our humble narrator, hitherto a libertine, responds to this new, firm hand with an immediate, enthusiastic, and total compliance. Given clear rules, Alex abides.

Maybe, then, like any naughty boy, Alex craves discipline and structure. Perhaps the problem on the outside was how easily he could dominate his ineffectual parents, and how he could use lashings of the old ultraviolence with impunity to thrive in a crumbling post-socialist moral wasteland.

No – I think it’s more accurate to understand this induction scene as our first and strongest evidence that Alex, a libertine but also a sociopath, is very capable of publicly conforming to society’s rules when he identifies that conforming to those rules is to his own significant benefit.

With this understanding, the orientation scene is integral to our comprehension of the second half of the film, in which Alex is “cured” by the Ludovico technique and re-enters society. Kubrick presents little compelling evidence that the technique is effective; Kubrick presents plenty of compelling evidence that Alex, a sociopath but definitely a perceptive one, recognises it is in his best interests to pretend the technique is effective.

Suicide attempt notwithstanding, time and again Alex’s circumstances are improved by playing along with this deception – precisely, by publicly feigning the effectiveness of the treatment at every opportunity, but more broadly, by outwardly conforming to societal expectation, regardless of his internal compulsions and intentions. Kubrick shows us that the elites with whom Alex becomes allied play along with the deception, too, because they can use Alex for their own gain – whether Alex is “completely reformed” is completely irrelevant. This leaves as the only dissenting voices Barnes and Chaplain Charlie – both are appalled by the “insincerities” of Alex’s cure and, unlike the jockeying politicians and intellectuals, both have no incentive to pretend otherwise.

The induction scene functions to show how Alex’s transition from boy to man is marked primarily by his recognition of establishment’s expectations for adulthood – play along. It doesn’t matter at all that Alex is at heart a raping, murdering, “ghastly wretched scoundrel” – if he can conform by at least offering a meretricious concealment of his abysmal impulses, he will be accepted and rewarded. FW

(One Last Thing)

In an abbreviated and restricted “year” of cinema attendance,

our five favourite films of 2021:

Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (Questlove)

The Father (Florian Zeller)

Another Round (Thomas Vinterberg)

Sound of Metal (Darius Marder)

The Green Knight (David Lowery)

(and if you’re wondering about First Cow by Reichardt

and Annette by Carax, so are we – didn’t catch ’em!)

Read Part 1 of our year in review for Luke Littleboy‘s analysis of No Time to Die and Ghostbusters: Afterlife.

And for a rundown of the other films that caught our eye in ’21, click through for Part 2!