To commemorate 30 years since it hit UK cinemas, Fletcher Walton explains some of the important ways in which the best action film of the ‘80s still stands tall in the cinematic skyline.

What makes Die Hard magnificent? It isn’t enough to say, “Willis”, or “Rickman”. It isn’t enough to talk about “the ’80s”. Die Hard is definitely better than almost any American action picture you could name, before or since. What makes it better? What choices made it better?

Die Hard is a colossal triumph of flexibility. So many of its strengths were forged in the furnace of the challenges of its shoot, where in the hands of incredibly talented filmmakers – producers Joel Silver, Lawrence Gordon and Lloyd Levin, writers Jeb Stuart and Steven E. De Souza, and particularly director John McTiernan and cinematographer Jan De Bont – each logistical hardship offered creative fecundity, the opportunity to constantly revise and reconsider, pushing for a film with greater depth, greater scope and greater character.

The first month of shooting was constrained by the limited availability of lead actor and TV megastar Bruce Willis, subject to a punishing schedule of Die Hard at night, Moonlighting by day. But in practice, it was this very vacuum that allowed for on-the-fly embellishment: of supporting roles, like Reginald VelJohnson’s finely-developed Sgt. Al Powell and his tear-jerking redemptive arc; and subplots, in particular the mordant depictions of news media and police procedure from which the picture’s enriching lip-smacking satirical zest then grows. Scheduling that ordinarily would have slowed down production was instead received as a challenge to dash about improving the film.

As shooting began, it was soon identified that hero (Bruce Willis) and villain (Alan Rickman) probably need to, you know, meet each other before they face off in the finale. As recounted by screenwriter De Souza, it was weeks into filming and during a pause for a shot change that an idling crewmember happened to ask Rickman if he could do an American accent, a question answered with sufficient affirmation that within literally minutes, writer, producer, director and actors were throwing together McClane’s confrontation with “Bill Clay”. A scene of fantastic tension, in hindsight utterly integral to the film, thought up in less than half an hour in the middle of the shoot because new information was disclosed in front of people who knew precisely how to use it.

So, ability is vital, and flexibility certainly helps – but what proved instrumental was the way these qualities hummed in concert with an artistic opportunism that manifested as a relentless dedication to impromptu improvement: an attitude of making time to try new ideas. Where does this resolve help Die Hard persevere on the long road to brilliance while lesser films make do with “good job”?

CREATING CHARACTER

All cinema is constructed – if it’s ended up onscreen, it was very likely a conscious decision with thought behind it. Perversely, cinema’s artifice is at its most effective when we don’t register it as artifice at all, and an author’s best work can be work we don’t even notice as work.

Inside only the first ten minutes of Die Hard, the quiet explanation of the character John McClane and the audience investment in him engendered by that unpacking is a case study in efficiency and precision from filmmakers that are obscuring the construction lines expertly. At the end of those ten minutes, we care about John and we’re ready to follow him anywhere. Let’s focus on those ten minutes. What decisions do the filmmakers take to make John “our guy”?

The second shot of the entire film is a close-up of John McClane’s hand gripped tightly around the armrest of his seat – he’s introduced to us as calm and taciturn but, before that, vulnerable and anxious.

Over the next few minutes, John is shown to be avuncular, open, self-reflexive, humble and human. This creates a little humour and a lot of empathy. His fear of flying, his easy banter, his failing marriage, his bemusement at his new environs – John is relatable, and he is also an underdog.

Structurally, the key to conveying John’s character early and quickly is the plot device of Argyle (De’voreaux White), the likable working-class novice limo driver, and John and Argyle’s first scene together, the ride from the airport, which functions as a naturalistic way for us to learn about the protagonist.

Upon meeting, Argyle confesses this is his first ever pick-up; John reciprocates, happily admitting he’s never been in a limo before, either, and as such he chooses to sit up front. John and Argyle are no longer driver and passenger, master and servant – John’s humility has immediately rendered them equals, riding together in the front, busting balls and playing tunes.

John takes Argyle’s probing personal questions with a wry smile, and with a little encouragement discusses his separation – as executed, this tells us about the character but also drives the plot, as resultantly, a sympathetic Argyle promises to wait in the garage for John in the event that the reconciliation fails and John needs a ride out to Captain Roberts’ couch in Pomona. Not only do we learn about John, we’re also given a reason for Argyle to stick around.

It’s a fun sequence, and it communicates so much of what we need to know in order for John to be “our guy” – his grounded attitude, his reduced circumstances, his humanity, his humility. The limo scene also presents his central dichotomy, one which find its reprise in McTiernan’s Die Hard With A Vengeance – a desire for family seemingly incompatible with his dedication to duty: “I’m a New York cop, I got a six-month backlog of New York scumbags I’m still trying to put behind bars. I can’t just pick up and go that easy.”

In those economical opening scenes, we learn a lot about John from his reactions to others – the filmmakers creating interactions for him to bounce off, though in a manner so relaxed as to be innocuous.

The tiny moment when John reciprocates the glance of the stewardess is assembled to tell us that John is just a little bit wolfish, a little bit unreconstructed blue-collar American male – recalling the words of Trent from Swingers, “the guy in the rated R movie, the guy you’re not sure whether or not you like yet.”

But his giant cuddly toy tells us he’s still a family man, a father and husband. As does his wedding ring, given its due importance in our very first frames with the character.

In the arrivals lounge, John witnesses a couple happily reuniting, in contrast to his own welcome – another tiny moment that elicits sympathy, as do his fish-out-of-water, affably baffled New Yorker-in-California reactions to his new east-meets-west locale.

In the late ’80s, sun-fried Los Angeles was a punchline, “the land of fruits and nuts”; at the same time, American cinema was outright preoccupied with the new-fangled economic threat of Japan –Gung Ho, Collision Course, Black Rain, Iron Maze, Rising Sun. Die Hard comments on both.

(Later on, the film’s subtext establishes that John, vulnerable and surplus, represents a retrograde alternative to those two modernising cultures – but he also stands apart from contemporary ‘80s musclebound superman like Arnie’s John Matrix or the later iterations of Stallone’s John Rambo. As our hero, “dumb Irish flatfoot” John McClane proves to be the quintessential cowboy: he is outnumbered, outgunned, surrounded in dangerous territory, hurting, alone; but, he has the love of a good woman and the fast hands of a couple of loyal deputies, he’s smart, resourceful, indefatigable, honourable, and, god damnit, he is American.)

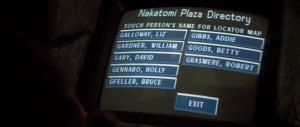

The last character notes of those introductory ten minutes, and two of my favourites, are seen as John enters the Nakatomi and briefly negotiates the computerised directory to locate Holly (Bonnie Bedelia).

Whether 1989 or 2019, apprehensive interaction with IT makes a character accessible, and it’s easy for an audience to see themselves in John. That empathy is compounded a moment later when it’s through this touch-screen console that John learns his wife has been working under her maiden name.

In screenwriting terms, and cognisant of the cinematic shibboleth “show, don’t tell”, it’s a sophisticated, engaging and almost wordless way in which to communicate two characters’ divergent opinions on their relationship and create emotion from the sudden confirmation of that gulf.

As a character beat, the quiet pain of John’s muttered, “Christ…” is classic Willis, the dramatic cherry on top of a sequence of strong, subtle cinema. With a few fragments of character work across three short scenes, John McClane is no longer just the lead –the filmmakers have done their job and made John “our guy”, and they’ve done it in ten minutes flat.

PLOTTING INTELLIGENTLY

There are a number of small plot points that need to stand to reason in order that the finished film maintain integrity.

Some of these were improvised during the shoot – it was only after enjoying the scenes with De’voreaux White as Argyle that the filmmakers decided to keep the character at Nakatomi Plaza, which they accomplished satisfactorily by showing that his fondness of John and enjoyment of chilling in an all-mod cons limousine was motivation enough to stick around; as such, McTiernan could then deploy Argyle heroically in the denouement to punch out Theo (Clarence Gilyard) and drive the McClanes into the sunset.

Some are almost incidental. In the Bill Clay scene, we might accept McClane’s suspicion of “Clay” as cop intuition and plain common sense. However, emblematic of the attention to detail throughout, the filmmakers earn that supposition with careful framing and editing of the offer and receipt of the cigarette, clearly emphasising how Clay’s acceptance of the unusual European smokes John has pilfered from the terrorists is conspicuous. Gruber is typically unflappable but McClane is onto him immediately – he is, after all, a policeman, with 11 years’ experience of figuring people out. As an audience, we don’t have to infer that – the filmmakers use their tools to make it very clear.

Let’s look at a plot point which is used to set up the climax: at some point in the film, Gruber must twig that Holly Gennaro is the wife of John McClane, and if it’s sudden and dramatic – and, as it proves to be, 28 seconds of perfect cinema – then all the better.

In the finished film, this is accomplished by hissable news anchor Dick Thornburg (William Atherton) tracking down Holly’s home address and broadcasting live from the family kitchen while Gruber watches on television.

I feel this is a thoroughly interesting contrivance with wonderful results. Jeb Stuart could have written the reveal in a dozen other ways, but he chose to involve television news; having involved television news, Stuart and De Souza then took that as an opportunity to extrapolate their plot device into a full-blown subplot of biting satire running through the entire second and third acts, as the audience is presented with nightcrawler Thornburg and all the pompous dimwits and callous ratings-chasers a depiction of his industry provides.

It’s a decision that exemplifies the artists’ comprehensive approach to painting to the edges of the canvas – in evidence, too, in all those lovely little asides, like a SWAT officer pricking his finger on a rosebush and Al Leong nervously stealing a chocolate bar.

And it illustrates one of the most important reasons for Die Hard‘s success – the story in the tower is strong, but so is the story outside the tower. All those memorable characters drawn to the Nakatomi and its siege – drawn by duty (Al Powell); by occupation (Dwayne T. Robinson); by professional opportunism (Thornburg); by the promise of macho excitement (Johnson and Johnson).

Each role performs a key mechanism in driving the plot forward but, thanks to the same assiduous approach to character and storytelling seen in the opening ten minutes and discussed earlier, each role also transcends their origin as plot device and becomes a vital, living, breathing part of that world.

DIVIDING LOYALTIES

In sharp relief to the remarkable lack of jingoism seen in these last 15 years of blockbuster casting – consider that by 2013, quintessential American heroes Superman, Batman and Spider-Man were all, without controversy or commentary, played by Brits – the Hollywood of the 1980s offered limeys only one part: charismatic baddie. Steven Berkoff in Beverly Hills Cop, Charles Dance in The Golden Child (later parodied by Dance himself in McTiernan’s Last Action Hero), Joss Ackland in Lethal Weapon 2.

All memorable, all enjoyable. But Alan Rickman – in his movie debut – changed the genre. His magnificent realisation of antagonist Hans Gruber created a new paradigm: this baddie is not just a worthy adversary, he is the very reason to see the film.

Rickman repeated the feat two years later with Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, and for perhaps 20 years it remained the convention that an action movie lives or dies by its baddie: Under Siege, Speed, Batman Forever, Air Force One; the concept reached its apogee with Face/Off, where both leads are simultaneously hero and baddie, and then its hysterical logical conclusion with Con Air, where everyone’s a baddie; but still continued into X-Men and Spider-Man, and on, until the event of the MCU firmly foregrounded heroes once again.

It’s in this context we should consider a plot point that is perhaps the film’s most important: these terrorists aren’t terrorists, they’re thieves. The decision was McTiernan’s, and it confirms his remarkable intellect and understanding of the medium, because it’s a decision that allows us to enjoy the bad guys.

McClane is our hero, and of course we want to see him prevail – this isn’t noir, we must see him prevail. But Die Hard is equally in love with his nemesis. We spend half the film with Gruber, and many scenes are not just from his point of view but are shot to support his point of view.

If that foments in the viewer a morality of increasing complexity – we are now sympathising with our putative aggressor – it should be no surprise that this very mindset is soon enough discussed within the text itself, as on television a psychologist expounds upon Stockholm Syndrome (confoundingly referred to as “Helsinki Syndrome”*) to news anchor Gail Wallens (’80s movie mom supreme Mary Ellen Trainor).

This deliberate and delectable mood of subversion culminates with the scene in which, as Gruber has predicted, a clueless FBI adheres to process and cuts the power…

As Michael Kamen’s score, which has been teasing delightfully for 100 minutes, finally unleashes Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” in all its majesty, the moment of triumph is unmistakably an exultation for Gruber and for the audience. The brainiac baddies have beaten the bonehead authorities and we’re backing them all the way.

McTiernan gave us permission to cheer for Gruber by making him not a terrorist but an exceptional thief – he is a rampant capitalist mordantly exploiting and lampooning anyone fool enough to concern themselves with something so limiting as a political ideology when cold hard cash is there for the taking. If anything, it probably makes Gruber an even better baddie – perhaps the only thing worse than holding violent radical philosophies is pretending to hold violent radical philosophies purely for profit.

Casting Gruber and his crew as pretend revolutionaries adds another dollop of satire to a pot already bubbling with delicious cultural commentary; more importantly, and especially in confrontation with a guileless police force led by incompetents, it allows the audience to root for the success of the masterplan guilt-free.

Three decades since release, we’re still enjoying Die Hard. It isn’t sentimental attachment, or adolescent crush. It isn’t ‘80s nostalgia. It isn’t just the performances and the casting. It isn’t because of its relative originality – its lone hero conceit is an inversion of McTiernan’s own Predator just 12 months earlier. (Indeed, the two films even share a scene of cacophonic gunplay as characters expend parodic amounts of bullets in a vulgar display of power against their invisible enemy.)

Die Hard remains a monolith because it is of the highest quality. This isn’t down to an ephemeral indefinable that makes old films good and new films bad – as I’ve sought to explain, its successes are precise and quantifiable. The ability and elan of its architects and builders was amplified by their unwavering dedication to using all time available to make each component as independently strong as possible, and what they constructed was a cinematic skyscraper.

In Century City, Los Angeles, the Nakatomi – actually the Fox Plaza, and only months older than the film in which it is immortalised – still stands; don’t be surprised if, in time, even it is outlived by Die Hard.