In 2017, Fletch saw 48 films at the cinema. We’ve chatted about a third of ‘em, here’s the third part of a rundown of the rest.

CULT ENCOUNTER #3: The Killing of a Sacred Deer

(dir. Yorgos Lanthimos)

Ain’t no one arguing Chris Nolan is an actor’s director; nevertheless, after two hours of this mesmeric, mordant derangement, to say Barry Keoghan was underserved by Dunkirk is the understatement of Hollywood’s 2018 – the lad Keoghan is tremendous in this, and Farrell is good, and Kidman is good, and I dunno how on earth Alicia Silverstone came onto their casting radar but she’s good, too.

Lanthimos’ previous, The Lobster, was strong, but it was a bit mannered and a bit arch. I fancy this nasty fucker goes even further. I sat there mouth open in delighted surprise at the horror of what was unfolding. I was appalled.

Prevenge

(dir. Alice Lowe)

For a comedy head that spent the second half of the last decade spinning Boosh, Barley, Snuff Box, Spaced, Modern Toss, Man to Man and Marenghi on repeat, it’s been a proper joy to survey with reverence, admiration and, of course, no little vindication as its assorted creators have transcended television to conquer British cinema and beyond. (Boosh director Paul King’s original Paddington took 268 million worldwide, which I’ve calculated could cover the costs of any Barratt-Fielding reboot for roughly 30,000 episodes.)

The Warp-Rook-Baby Cow set is a crew of bracing and singular originality united by a disarming sincerity in approach, a fervency towards cult pop culture, an aficionado’s accuracy in homage and pastiche, and a shared casting pool headed by Marsha and Tyres from Spaced. Twenty seventeen was a banner year: Prevenge, Free Fire, Mindhorn, Baby Driver, Paddington 2 and The Ghoul. I’ve already stated my disappointment in Mindhorn – but in that dynamic sextet its failings are comfortably offset by two of the best films of this decade.

Alice Lowe’s micro-budget directorial debut Prevenge is a worthy addition to their glorious canon. I can’t yet speak to its enduring quality – partly because it’s 14 months since I saw the thing – but it is engaging, it is unusual, it is committed, it is an honest articulation of an interesting point of view, and all of that is exactly what we’re after.

Moonlight

(dir. Barry Jenkins)

Bottles it at the last minute, and there’s a few false notes (like Naomie Harris’ thankless role as a one-note crack mama, and a thugged-out dope-dealer Fiddy-looking protagonist who the audience is expected to believe hasn’t had a single intimate experience in 15 years), but otherwise, largely ace.

The Evil Dead

(dir. Sam Raimi)

A few weeks before I was born in late, late summer ‘83, Raimi, Tapert & Campbell’s debut, The Evil Dead, was banned from home video, physically removed from shelves, rental shop owners prosecuted, and any distributor or dealer selling The Evil Dead on home video faced being sent to fucking prison for “disseminating obscene materials.” Swamped by a moral panic, the first cinema release by that besuited, unassuming Michiganian who you know as the captain of Sony’s $2.5 billion Spider-Man franchise was deemed a “video nasty” and prohibited from exhibition anywhere in the UK until eventual reclassification in 1990 with 120 seconds cut.

Three decades later, the fuss remains understandable and pleasingly, the promise and prowess shown by its fledgling filmmakers undeniable. Bolstered by the immersion of cinema exhibition, The Evil Dead was immediately a better film than I’d credited, no longer just a strong blueprint for a superior sequel but on its own terms a startling success of nascent, unrefined cinematic ambition. Raimi – the multiplex needs you more than ever.

Atomic Blonde

(dir. David Leitch)

A fervid neon burst of glasnost pulp, an exuberant celebration in both sorrow and joy to an exciting cultural moment of opportunity and emancipation.

An irresistible cinematic tribute – I’ll give you just one bastard example, the subtitles are in Franklin Gothic Demi – that resurrects prosaic nostalgia to be reconditioned as delicious detail and applied cool.

A neo-noir spy actioner put together with consideration and elan, littered with fight scenes that knocked my socks off.

A dope debut proper for stunt coordinator-turned 1st AD-turned solo helmer Leitch.

An uproarious reassertion that when he takes his pointy finger down from his bloomin’ temples, X-baldy McAvoy is still the actor that threw up Filth.

A triumph, an absolute triumph, for Furiosa herself, Charlize fucking Theron.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

(dir. David Lynch)

Luke’s just about ready to excommunicate me for missing the astonishing new season but at least I took the opportunity to genuflect before the prequel at the Prince Charles. For a cineaste who is Lynch-lover first and Bookhouse Boy second, what a picture it is.

Deploying the litany of Peaks characters with restraint and exceptional storytelling precision, it’s an uncomfortable, upsetting meditation on trauma and suffering. I’d say it actually benefits from its cutely contemporary casting (Kiefer, Chris Isaak, Pamela Gidley) and Sheryl Lee’s lynchpin performance as the Laura we never knew is a knockout.

Visually memorable, aurally magnificent, the project is a courageous, transgressive transition from the limits of the small screen to the liberation of cinema that at time of release was largely lost on an expectant, uncomprehending public whose collective negative opinion can clearly go fuck itself.

Ironically, the television broadcast of last year’s aptly-named The Return probably demonstrates that 25 years on, the landscapes have transposed, and filmmakers are increasingly desirous of a pivot back from cinema.

Detroit

(dir. Katheryn Bigelow)

Diverting to consider that for an intrinsically American story, a director praised for her verisimilitude chose to centre the main cast with three recognisably English actors and it wasn’t even mentioned. Is it cos we’re cheaper or is it cos we’re just fucking better? I imagine scores of generically handsome but artistically uninteresting Yank wannabes feverishly plotting how to present a diversity argument along the lines of #hollywoodsobritish. This clutch – John Boywalton, Eyebrows and Her Off Game of Skins – are terrific, as are Australian Ben O’Toole and Irishman Jack Reynor, and I was pleased to spot a tiny role for turn-of-the-century scene stealer Glenn Fitzgerald.

Zero Dark Thirty was two-and-a-half hours and I would have happily taken another 20 minutes – I think it’s a masterwork, I think even Jim Cameron could consider it might be the best thing he or Kat have ever delivered. Detroit isn’t much shorter but this time I needed another 20 minutes, split equally at either end of Bigelow’s monolithic reconstruction of the Algiers Motel incident, to spend longer in that time and with those characters. As it is, as strong as this picture was on first watch, the centrepiece takes up too much of the running time – I wouldn’t shorten it, rather I’d like to see the first and third acts lengthened.

The Breakfast Club and Planes, Trains and Automobiles

(dir. John Hughes)

How many of your favourite films have you never seen at the cinema?

I grew up on Landis, Carpenter, Hughes – the Holy Trinity of Johns. I’ve seen Animal House, Trading Places, Big Trouble in Little China, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off perhaps 20 times each. There’s no other art, no painting or play or poem or even prose, that I’ve known for as long and returned to as often as I have these movies – but I’ve seen none of them at the pictures, ever. It was at home on video when I was 9, 10, 11 that I absorbed, memorised, revised, devoured these films before I even knew what film was, and without doubt consumption at that juvenile level has distorted my perception of what they are as cinema. I’ll warrant the same is true of you, too. You’ve been watching Ghostbusters for almost three decades. How many years was it before you realised who shot it?

When finally I saw The Blues Brothers on the big screen, and The Thing and Halloween, and, last year, Planes, Trains and Automobiles and The Breakfast Club, the medium revealed so much that was new to me.

Superficially, the manifold marvellous details all but imperceptible on the 20” CRT screens of our adolescence – like f’rinstance, as Del and Neal leap out of bed, I noticed for the first time a set of old, grimy and unmistakably coital handprints wiped into the wallpaper either side of the picture above the bed’s headboard.

Critically, in a fresh context that proved revitalising, I was deliberately engaging with these works as cinema, able also to use my familiarity with them to look past the plot and the gags and the one-liners and admire and analyse their design and construction as I never could have done as a child.

And so in Planes, Trains and Automobiles it’s easier to recognise how often John Hughes uses filmmaking to tell a joke – uses precise movement and placement of his camera; uses simple close-up inserts; uses editing and music in a complimentary interaction to create a metronomic tempo over which to play the scene. I reflected that so many modern comedy directors don’t do that, possibly don’t know how to do that. They call “action” on improv comedians and the lenser hits record; John Hughes directs.

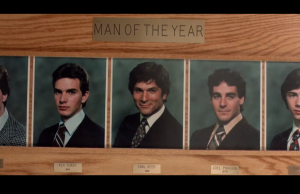

And so in The Breakfast Club, I saw the blatancy of Andrew’s fast-forming crush on Allison, and the delicate notes of the performances by Sheedy and the ‘Vez. As they walk to get drinks, how first Andrew is leading the frame, “So, what’s your poison?”, before Allison’s answer, “Vodka”, asserts herself. She moves past him, taking control as he cedes it; disarmed, he moves to the wall as the shot pins him to it, opening him physically as he opens himself emotionally, inviting Allison and the audience in as he speaks honestly about his lack of self-determination.

Next time a pub bore clichés off about how it’s a “filmed play”, tell ‘em this scene. Tell ‘em the opening montage of perfect tableaus. Tell ‘em the endless careful medium close-ups and the patient compassion and empathy they engender. We care about Neal and Del and Brian and Allison and Claire and Andrew and Bender because Hughes uses cinema to makes us care.

Drop by later this month for our last look back at 2018 – by now you’ve surely had enough time to catch almost every one of ‘em!