Talking about camera shots can be as dancing about architecture, so to supplement our recent discussions on the Electronic Labyrinth, here we’ll use pictures and prose to try to better explain a few things we enjoy about how Spielberg and DP Dean Cundey conduct the cinematography of Jurassic Park.

Close-ups and inserts

Let’s kick off at the beginning. Like Friedkin’s Sorcerer, the audience hits the ground running with a globetrotting triptych of short sequences setting up the players and their relationship to Jurassic Park. The opening shots of the film are on Isla Nublar and show the accident that enables the entire plot. Without stars, without deploying ILM, largely without dialogue, Spielberg creates an atmosphere of foreboding and intensity through mid-shots and close-ups on the assembled nervous handlers.

(Five years later, Spielberg and Janusz Kaminski would use basically the same shots for the same reason to open the flashback in Saving Private Ryan.)

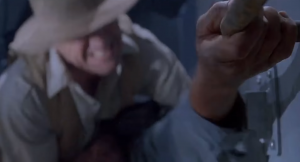

Systems fail with terrifying results, and horror is generated through close-ups and extreme close-ups as an unlucky worker is killed by inches. Note how full the frame is – the hand in close-up creates a dreadful desperation and urgency, while out of focus but equally weighted we can identify the recently-introduced Muldoon struggling to save the gatekeeper.

The close-ups thrill us while at the same time the reaction shots do the character work. During the attack, two quick inserts – perhaps four dozen frames – is all that’s required to establish Muldoon and the lead ‘raptor thematically as deadly adversaries, intrinsically linked. The economy demonstrated is typical of Spielberg’s work on this picture, where thorough preparation of shot selection so often obviates and supplants our notions of conventional action editing.

Lots of people in shot

There’s an energy about Spielberg’s crowd scenes that’s nourishing to the eye. This throng of extras and their arrangement for the camera brings activity to a scene which in other hands would likely feature only Grant, Ellie and one or two bit-parts – such a staging would function similarly but definitely less successfully.

The frame is composed and yet in execution feels casual. There are more than a dozen faces in this shot and most are visible throughout.

That continues through the scene…

..and as well as looking dynamic, it advances character:

surrounding Grant positions him centre of the frame, which establishes him as important, and provides him an audience, which affords him authority. Why do we respect Grant? Well, one reason is because we can see all these cats respect Grant – they may titter when he mentions his avian theory, but he settles them immediately with a relaxed, charming assurance. And when he threatens to gut that sproglet with a fossilised death claw, such is their ardor the assorted students burst into spontaneous applause (I think).

Several people in conversation

In the scene outside that prison for dinosaurs, the challenge is involving six characters of equal importance in Muldoon’s explanation of the lethality of the ‘raptors, and I find the choices of Spielberg and Cundey very interesting. Two static wide shots, basically masters, with Hammond as the pivot – you’ll notice that when the shot cuts briefly from one side of the conversation to the other (the scene functions as a particularly wide shot-reverse shot), Hammond’s position in the frame remains exactly the same.

The sequence runs for more than a minute. There are no inserts or close-ups to highlight or emphasise Muldoon’s grim message – instead, having designed and blocked well, Spielberg’s confident he can roll camera and hold our attention simply by allowing the actors do their thing, and clearly that confidence was sustained both on-set and in the edit suite.

I’ve long wondered if that’s one reason why Spielberg shares with Kubrick a notable dedication to veteran British actors. Christopher Lee, Paul Freeman, Denholm Elliott, Philip Stone, Sean Connery, Julian Glover, Ben Kingsley, Bob Peck, Dickie Attenborough, Anthony Hopkins, Nigel Hawthorne, Jim Broadbent, John Hurt, Daniel Day Lewis and Mark Rylance can be relied upon to turn up knowing their lines and get it right without any bother. (Incidentally, nine of that lot have been knighted for services to the arts.)

Famously, Spielberg genuinely considered the best actor in the world to be humble Lancastrian Pete Postlethwaite, with whom he worked back-to-back on The Lost World and Amistad. Watching what Pete can do even with supporting turns in escapist fare like Dragonheart, there’s no compelling evidence to the contrary.

Camera creates action

Spielberg’s camera moves precisely, with great impetus, and it has a clear destination. Within carefully designed longer takes, cuts and inserts are rendered largely unnecessary because close-ups and pull-backs are already included in the devised shot. Pans and zooms pace and delineate the action, serving as identifiable stages within a single continuous movement on its way to a climax, at which point we get the cut (and catch our breath).

Look out for how often Spielberg’s shots end with the camera tracking in to a close-up, or a character moving towards the camera to force a close-up – the frame itself is used to communicate and create emotion, not only the stuff that’s going on inside it.

(In contrast, Christopher Nolan works from a quite different principle – he and Lee Smith often edit shots to cut before a climax, mid-movement, especially in The Dark Knight, which admittedly does have a theme of escalation over purpose. It’s redolent of Malick, and though I admire it, it can be frustrating, and occasionally baffling, and even technically wrong.)

One effect of Spielberg’s shooting style we really dig is shots in which characters appear to roam freely, dictating the frame with their own actions, their movements within the shot also creating a terrific sense of breadth and depth to the space. In this lovely scene, Spielberg includes other intelligent ways for the eye to both gauge and explore the space – the fences help explain size and proportion, while the long beams of the flashlights have the effect of stretching and broaching the frame.

Another effect is one of forward progress – these fluid jib and dolly sweeps maintain momentum. It makes me think of a rally car shifting through gears, rounding a corner, over a bridge, down a straight – each small precise action a part of a longer journey.

Ellie and Muldoon’s arrival at the aftermath of the Rex attack typifies this kinesis. In the first shot, the characters explore their own frame for the benefit of the audience as much as their understanding of the attack. Ellie moves into close-up while Muldoon remains out of focus in the background. Both have found Gennaro, which Spielberg captures in a manner just as gruesome and far more dynamic than if his eviscerated remains were ever in shot.

They continue to interact with one another and both are still balanced within the frame and of equal importance to the shot, which ends with the pair scanning the surroundings expectantly with flashlights.

That action opens the next cut, where a mid-shot on Ellie and Muldoon pans down to reveal Malcolm injured on the ground a few feet away.

The pair step to Malcolm and the pan moves laterally to follow Muldoon’s flashlight down to Malcolm’s wound and then reverses and back up to his face as he quips sarcastically.

A roar directs attention offscreen and the camera pans back up with the flashlights – Malcolm is excluded from the frame as Ellie asks, “Can we chance moving him?”.

Spielberg ends the scene comically as the shot answers Ellie’s question – Malcolm abruptly re-enters the frame, with the effect of taking control, and replies, “Please, chance it(!)”

That first shot runs 42 seconds, a remarkable duration, and the second about half that span, but neither feels like a “long take”. They’re just a simple, immersive way to capture the action.

Here’s another example, even more modest – Malcolm, prone in the jeep, recognises the T-Rex approaching.

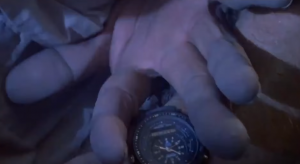

The shot begins on Malcolm waking up. The camera pans from Malcolm straight down to a Rex footprint and the puddle of rain created in it, in which Malcolm is reflected, out of focus.

The puddle shakes with the impact tremor of the Rex’s footstep, and the shot refocuses to capture Malcolm’s concern, then cuts.

The shot has three parts: an opening, in which the threat is introduced; an event, in which the threat is confirmed; and a climax, in which the confirmed threat creates a response, escalating the tension and progressing the action.

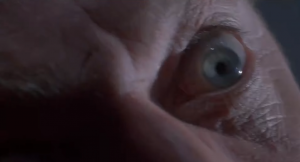

Face acting

Emotion can be communicated, imprinted and embellished on the audience very simply with effective reaction shots. As viewers, we’re amazed by the brachiosaur, shocked by the velociraptors and petrified by the Tyrannosaurus Rex because Spielberg is sure to show us that his characters are amazed, shocked and petrified – and Jurassic Park features some wonderful reaction shot face acting.

A pal of mine who has worked in combat zones told me that hour-to-hour going about his job he rarely felt imperiled – it was later, reviewing video, when he saw his colleagues reacting to peril or in peril themselves, that he was struck by the danger of the environment. I reckon that applies to cinema, too – what makes a dinosaur threatening is that the characters in the film are shown finding that dinosaur threatening.

Those reaction shots are an economical and efficient method of amplifying the mood of every scene. The special effects of Jurassic Park are fantastic, but so much of the cinematic heavy lifting to create tension and danger is done through acting and editing.

On set, the raptors’ feeding amounts to several oversize houseplants being shaken by a greensman. In the film, the threat posed by the raptors’ is communicated through the incredulity of the onlookers. We don’t even have to see the dinosaurs to be afraid, and indeed not yet seeing them heightens their mystique and our trepidation.

Also useful, the characters share their frames with the thing to which they are reacting – the shaking foliage, which was confirmed as the stand-in for the ‘raptors in the establishing shots. And here again, for Hammond’s reaction shot he shares the frame with the things to which he is reacting, his guests.

(Along a similar line of argument, check out the jeep chase – every shot of the Rex includes the vehicle, which is incredibly helpful in conveying size and perspective. Our response is intensified if we understand to what we’re responding.)

Put us in the picture

Another smart, simple technique immerses the audience in the scene by placing us alongside the characters to see what they see, how they see it, as they see it.

In the Rex attack, a shot begins with Grant and Malcolm casually reacting to Gennaro’s dash to the lav, and the camera’s positioned alongside them.

It records their low-key comic response, then pans with them as they turn their heads to the right and simultaneously characters and audience watch the electrified fence ripped from its posts.

Here, I think the shared vantage does a couple of things: the view of characters and audience is restricted by the car windshield, and that creates tension; and the camera placement puts us in the car with the characters, and that increases our own feelings of danger and peril.

Set it up and let it roll

We’ll close with some shots from The Lost World, Spielberg’s second film with cinematographer Janusz Kaminski. Spielberg collaborated twice with Cundey, twice with Vilmos Zsigmond, three times with Douglas Slocombe and three times with Allen Daviau, but to the exclusion of all others it’s Kaminski who has been his director of photography for the last 25 years.

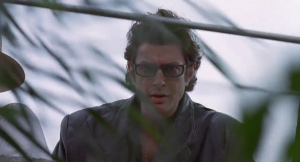

I like it when Spielberg picks a smart vantage point and sticks with it. Here, for a straightforward dialogue scene, he and Kaminski set up the players down a deep field and hold for over a minute. The careful camera placement has ensured close-ups are unnecessary. As “long cuts” go, it isn’t ostentatious or energised – it’s simply a visually arresting position from which to view these events.

This shot also reflects the plot and informs the storytelling. The frame is dominated by the film’s threat, Ludlow and his corporate machinery, which dwarfs Lex and Tim, our familiar innocents from the first film, who are lit to evoke happy memories and are then physically removed; Malcolm is positioned as their protector and then functions within the shot as a conduit between the optimism and wonder of the first picture and the impending darkness and exploitation of this picture.

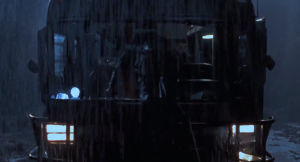

Here’s another long take, and rather a fun one, during Eddie Carr’s rescue of Sarah Harding’s good guy gatherer team. Eddie arrives and Spielberg establishes the situation – the trailer is perched on the cliff edge, the side door won’t open, the ground is muddy, it’s raining heavily.

The next shot is a tracker that begins as Eddie leaves the trailer. In one crane shot that starts from behind Eddie’s 4 x 4, the shot captures Eddie as he moves to the foreground to his own vehicle to grab rope…

..tracks to the right and past the vehicle to show Eddie at a tree stump around which he ties the rope…

..repositions behind Eddie as it follows him through the smashed windshield and into the mobile lab…

..stays behind him as he moves through the lab (here, he’s turned back for a second to check the rope)…

..and finishes up going “over the edge” to frame Harding, Malcolm and Van Owen as Eddie, top right, throws them the other end of the rope.

The shot last 48 seconds, an eternity in modern Hollywood cinema, but personally I don’t find it ostentatious. In execution, it’s a filmmaker choosing the most efficient way to show Eddie’s actions while also establishing the topography of the scene – Eddie’s vehicle, the stricken trailers, the “corridor” of the lab, the rope acting as their lifeline, all of which are crucial to our comprehension of the ensuing action sequence.

Spielberg vs Not Spielberg

Throughout this article, I’ve chosen not to draw direct comparisons between what Spielberg does and what modern directors do, because it’s not the point I’m making, and because it’s a little bit glib, and because it’s too easy to argue it’s largely apples and oranges. Having said that.. this is a direct comparison between The Lost World and Jurassic World.

Here’s a short shot that depicts Eddie driving to save his team. It’s a straight on medium shot with a slight shake to the camera. Looks like it was done in a car wash in three minutes.

The shot is the midpoint of a long, tense action sequence set on a cliff edge in which the leads have almost been thrown to the ocean and now hang perilously waiting for rescue, so how is that intensity sustained for this brief cutaway? With rain lashing, wipers flashing, palms crashing, terrain jolting the car up and down, and through it all Eddie focused on his task. It’s most certainly game time.

We’ve a similar set of circumstances for a shot in Jurassic World, tensions rising as Claire speeds back to HQ from the apparently empty Indominus paddock – apparently the deadliest fucker in the park has miraculously escaped. The shot is a pan from right to left lasting eight seconds, starting as a mid-shot of the speeding Merc and swinging around the front right of the car and up to the passenger window to rest on Claire shouting down the phone.

What’s captured on screen looks frankly delicious – the greens are verdant, Claire’s crimson barnet pops, and her white garb against the onyx interior of the Merc is terrific. DP John Schwartzman shot the three films that propelled Michael Bay to megastardom, so he knows how to light and colour a shot to make it “cool.”

But does it sustain tension, or evoke excitement? Not to any great degree, not really through any cinematic dexterity, not nearly as well as what we saw in The Lost World.

Any excitement is derived only from two elements: the speed at which the car is shown to be moving, which is achieved prosaically with a wide shot showing the entire car and that it is going fast; and the camera’s sweep from bonnet to interior, which might be more thrilling if the shot felt like a set-up on location that took time to capture rather than a set of composites sewn together digitally with Bryce Dallas Howard acting against a green screen, (and, it must be said, framed flatly). On reflection, both those elements – showing the entire car and the camera swoop – feel obvious and lazy, and they don’t evoke excitement in me at all.

In contrast, Spielberg and Kaminski choose to reflect the determination of Eddie and the speed of his vehicle through only its frenzied physical interaction with the environment – the rain, the dark, the trees, the sodden forest floor beneath the tyres. This approach is less bombastic, but in practice feels more visceral – as an audience we’re immersed in the tropical storm Eddie is battling against; and, it achieves more – in understanding the adversity Eddie faces, we consider him both more empathetic and more heroic. I also enjoy how the success of the finished shot is intrinsically cinematic: Richard Schiff could be sitting on a tea chest behind half a car bonnet under a sprinkler in a garden centre, but through the frame of cinema he is under siege in a race against time.

(One last thing)

And that’s why he makes the big bucks.

We’ll probably stick this lot in a video soon enough, but until then, use the comments here to let us know when and how Spielberg has grabbed you and we’ll take a look ourselves.

Further reading:

You can listen to our podcast that celebrates Spielberg’s impact on the franchise as a whole: Jurassic Park’s Sequels: How Do You Solve a Problem Like Crichton and Spielberg – The Electronic Labyrinth Podcast

Luke writes about Why Jurassic Park Isn’t Really About Dinosaurs

We re-examine Colin Trevorrow’s Jurassic World and find that it may well have been the Jurassic Park movie we needed at the time

Luke and Fletch review Fallen Kingdom on The Electronic Labyrinth Podcast