In 2017, Fletch saw 48 films at the cinema. We’ve chatted about a third of ‘em, here’s the second part of a rundown of the rest.

The Light Between Oceans

(dir. Derek Cianfrance)

The first film I saw in 2017 was, fittingly, a holdover from late 2016, casting me as a cinemagoing Janus. It’s a sober drama of contrition and loss by the director of Blue Valentine and the cult masterpiece The Place Beyond the Pines, and what’s stayed with me is the immersive realisation of the weather raging all about its resolute lighthouse. Let’s doff our caps to hot young Aussie DP Adam Arkapaw (True Detective 1, Macbeth) and the sound design team led by Jacob Ribicoff.

Loving

(dir. Jeff Nichols)

Another lovely low-key delight from Nichols, depicting with restraint and humane stoicism the relationship of a very ordinary working class couple, played by Ruth Negga and Joel Edgerton, living through adversity with all the quiet patience and abiding strength inherent in the profession of Edgerton’s bricklayer protagonist. Negga is masterful.

Logan

(dir. James Mangold)

Irrespective of brand fidelity, it’s personally very satisfying to see a small-scale X-Men picture of adult concerns in a plausible reality imperilled by degeneration and vulnerability, rather than unkillable costumes saving the world from unstoppable blue-and-teal god men. Also, the long-awaited, well-earned 15-certificate means they can cuss and brawl like a Walter Hill film, and so the gruelling action scenes – including, at last, Wolverine in berserker mode – are a highlight only bested by the genuinely thrilling execution of a sequence in which we find out what the fuck happens when the world’s most powerful telepath has a full-on brain seizure.

Victoria

(dir. Sebastian Schipper)

Eins verrückte Nacht in eins verrückt Schuss als zufälliges Zusammentreffen in der Glut der Mondlicht lädt Laia Costa’s unabhängige Ibererin in eine berauschende Grenze zwischen Tag und Nacht und Leben und Tod auf den Straßen Berlins ein. Einnehmend Tempo und emotional echt.

The Disaster Artist

(dir. James Franco)

I’m going to spend the third and fourth quarters of 2018 trying to do the voice. “No, Stanislavsky not dea’. I just speak to him, for your information. What d’you think I speak to, ghos’?!”

Colossal

(dir. Nacho Vigalondo)

Aside from the overall accomplishment of pulling off the genuinely eccentric kaiju-meets-Reitman’s Young Adult premise with uproarious panache, there was truth in this, both leads excelled, and I’ve rarely seen a more accurate evocation of a fucking bully. Incidentally – and this reads like a list of things we love – it was the late Jonathan Demme who inspired his artistically hungry Rachel Getting Married star Annie Hathaway to detour in this unexpected direction, by screening for her – you’re gonna like this – Wheatley and Jump’s A Field In England!

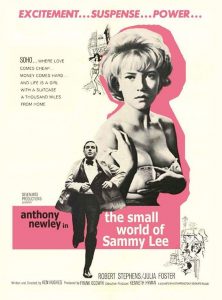

CULT ENCOUNTER #2: The Small World of Sammy Lee

(dir. Ken Hughes)

In this gem from 1963 that I took a punt on at a Regent Street Cinema revival weekend, song-and-dance-man Anthony Newley, best known to fans of unwatchable madness as Captain Manzini from The Garbage Pail Kids: The Movie, is a passing Jew about to fall off the lowest rung of the showbiz ladder, three hundred in the red and running out of time around a seldom-seen early ‘60s Soho at the liminal as Beat became Beatles, fascinating and unpleasant and vibrant with vice.

As our capital’s identity is incrementally sacrificed at the altar of foreign investment, I’m increasingly excited by depictions of old London’s hidden spaces and lost locales, and this one’s a cracker. Lensed on location by Get Carter’s Wolfgang Suschitzky (whose similarly impressive son Peter shot The Empire Strikes Back and near a dozen films with Cronenberg), we’re wheeler-dealing in the dark of snooker halls, striptease shows and basement clubs, musicians, Macmillan men and mobsters.

Then, back topside, bleary-eyed and sleep-deprived, pounding the pavements of a shabby central London, Soho incongruous in daylight, mixing among merchants and Mod enforcers, World War II veterans and Windrush West Indians, where every backstreet business and hard-nosed proprietor offers opportunity for illicit gain.

Even in this mercantile milieu of constant transactions, the ever-popular Sammy seems surrounded by good-hearted pals all but begging to offer slightly misplaced benevolence – Wilfrid Brambell’s faithful assistant, Julia Foster’s starstruck ingenue, Toni Palmer as the brass in the bedsit next door.

Instead, conveying a building desperation simmering below the upbeat façade of an experienced chancer, Newley’s Sammy barrels breathlessly about the field of play, darting from deal-to-deal and payphone to punter like a sprite in an RPG – sell watches at ten bob to buy glassware for twenty, flog glassware to cover horserace, run thirty quid to Peter and come back with fifty quid for Paul – in service of the kind of unsustainable hustle that characterises an aggregation of bad habits and bad decisions reaching overdue crisis. I feel like saying more, but I don’t want to ruin the surprise. Do yerself a favour – pair this with last year’s similarly grotty Good Time and get back to us.

Next week: Part Five!