Jonathan Demme is among the most important North American filmmakers of the 1980s, of the 1990s, of yesterday, of next week, of 30 years from now. Jonathan Demme cannot stop making features and documentaries and performance films about humans he finds fascinating, and the features and documentaries and performance films he makes are as involving and joyful and esoteric and vital as their subjects. To accomplish that, to time and again successfully use a (all stripes of filmmaking) to communicate to b (whoever happens to be watching) his argument for why they should be captivated by c (a gas station attendant who may have met Howard Hughes/a monologist explaining his relationship with Cambodia/Robyn Hitchcock playing inside a shop/a relapsing addict at a wedding), requires astonishing ability. It is my firm belief that out there, in the world, day-to-day, anyone who ever cared about film should be regularly, casually, without affectation, talking about Jonathan Demme, on the tube home, over dinner, at the football, in the queue for the toilet, “You know what, though – how bloody good is Jonathan Demme?”

What makes me dig Jonathan Demme? What makes me love Jonathan Demme?

Jonathan Demme loves people and peoples. He’s tirelessly inquisitive about talented individuals. He’s excited by subcultures and counter-cultures. He’s attentive to isolated individuals, men and women on the fringe of a group, men and women anxious not to be defined by the echo of a single traumatic event. He pays particular attention to women: from his lauded, subversive’s take on exploitation in Caged Heat and Crazy Mama through Angela de Marco, Clarice Starling, and Sethe, and finally to Kym Buchman and Linda/Ricki.

He pays particular attention to blackness. West Indian Sister Carol toasting through the credits of Something Wild and dropping us a wink as Married to the Mob reaches its happy ending; the close quarters kineticism of the Millers’ lower-middle class kitchen in Philadelphia. In contrast to those joys, the marginalisation of returning soldiers in the post-war Los Angeles of Devil In A Blue Dress and the dystopian aftermath of Iraq 2 in The Manchurian Candidate and the unremitting ghastly legacy of slavery in Beloved. Finally, wonderfully, the absorbing melting pot celebration of Rachel Getting Married. Demme’s three collaborations with Denzel Washington resulted in three of that actor’s best films and as a producer Demme has been dedicated to telling black stories. Even in the Anglo-Germanic environments of The Silence of the Lambs, Demme applies the avuncular Frankie Faison as orderly Barney, a paragon of politeness respected by even Hannibal Lecter, and as Starling’s fellow cadet and confidante casts Kasi Lemmons; indeed, the breathtaking sequence of Lecter’s escape reaches its crescendo with a frantic shot of Lemmons’ Ardelia racing down the corridor to deliver the news.

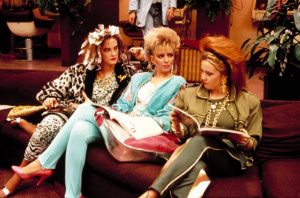

Elsewhere, Demme’s irresistible warmth for subculture finds full song in Married to the Mob as he revels in the rich possibilities offered by the gaudy milieu of New Jersey Mafiadom’s Roman Catholic mores and Italian-American tacky glamour. Levittown tract housing with marble and gold interiors, closets stuffed with stolen stereos, boxed kitchenware in teetering stacks. Fedoras, overcoats, scarves and three-piece suits for preening kingpin Tony “The Tiger” Russo; Hawaiian shirts, polos and leisurewear for his ’50s throwback guys; power pastel pant suits, loud blouses, stirrup leggings, animal print and big, big hair for their ’80s beauty parlour molls.

Demme’s next film, The Silence of the Lambs – incidentally, who else but maybe the Coen Brothers could work these projects back-to-back? – offers as protagonist Clarice Starling. Like Mob‘s Angela de Marco, she is a self-possessed working class female quietly desperate to surmount the trappings and tragedies of her upbringing.

Starling, a woman-in-a-man’s-world, “one generation from poor white trash”, who, like the grey, semi-rural small towns of her investigation, is presented with clear-eyed and deeply-felt compassion. In both pictures, people and place are observed humanely and the honesty and sensitivity with which they are presented is impactful – in Lambs, recall the kindness of Clarice’s interactions with Stacy and Mr Bimmel and the elegy of Frederica’s bedroom. Jonathan Demme loves his characters, he loves his heroes and his villains, he loves his leads and his bit-parts, he loves his characters.

Jonathan Demme loves his character actors, too, and has always retained a film fan’s adolescent affinity for the gratification of a cameo. Throughout his career he has filled out his supporting casts with his repertory – Harry Northup, Anna Deavere Smith, Paul Lazar, Obba Babatunde, and most memorably, Tracey Walter and Charles Napier – while also finding regular bit-parts for mentor Roger Corman and long-time producers Kenneth Utt, Gary Goetzman and Edward Saxon.

Jonathan Demme loves music, and what he loves is electrifying. It’s achingly apparent that few decent American filmmakers also possess an understanding of anything interesting and relevant in art rock and indie rock and contemporary music in general – some exceptions: Hal Hartley, Sofia Coppola, Gregg Araki, Peter Berg, maybe Kelly Reichardt – which makes Demme’s open-hearted, honest appreciation all the more enjoyable, and it is to be enjoyed. Hip? Cool? Important? Yes, yes, yes, but why are we talking, this is a party, for chrissakes, get on the damn dancefloor!

I fell for The Feelies before I’d even listened to The Feelies, before I’d even seen them front and centre in Something Wild, because Demme stuck “Too Far Gone” in the similarly exuberant Married to the Mob as part of a credits-long montage I watched compulsively because to my amazed pre-teen eyes it seemed to comprise a secret alternate cut of its own film and I didn’t know films could do that! Mob also contained his first use of Q. Lazzarus’ “Goodbye Horses”, foregrounded to unforgettable effect in Lambs. As was “American Girl” by Tom Petty. As was “Hip Priest” by The Fall. Big Audio Dynamite, New Order, Big Youth, Les Freres Parent, The Judy’s, X, Pixies, Debbie Harry, Colin Newman – a Demme soundtrack is a mix-tape given to you in 1987 by your older sister before she left for uni, and where music’s concerned we haven’t yet even considered: career-best collaborations with David Byrne, a welcome preoccupation with Robyn Hitchcock, three documentaries with Neil Young, two nominations for Academy Award for Best Song by different artists for the same film, a delightful clutch of music videos, and perhaps the greatest performance film of all time, Stop Making Sense.

Jonathan Demme can’t resist casting musicians, too – the aforementioned Sister Carol in Married to the Mob, Danny Darst in The Silence of the Lambs, Chris Isaak in Mob and Lambs, Robyn Hitchcock in The Manchurian Candidate, Tunde Adebimpe in Rachel Getting Married, Rick Springfield in Ricki and The Flash, and I really could keep going.

Jonathan Demme is in love with musicians and their music and their muse and he takes every opportunity to share it. So he turns us onto obscure new wavers Suburban Lawns, he redefines the form with Talking Heads, he shoots triptychs with Neil Young, he has a 65-year-old Meryl Streep learn to play guitar while at the same time a 65-year-old Rick Springfield learns to act, and, to make it really clear, he’ll spell it out for us with Maria Calas and “La mamma morta”, have Andrew Beckett literally talk us through the plangent ecstasy of performance as Joe Miller, once ignorant, looks on in wonder, in pity, in compassion, in understanding, enlightened.

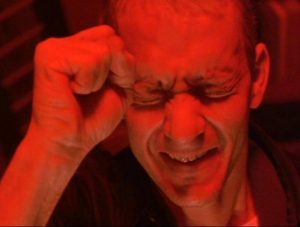

Jonathan Demme is unobtrusively, habitually artistically exciting, both in form and in truth and often in using form to better find truth. Watching his video for “Streets of Philadelphia”, halfway through it’s fair staggering to both see and hear a motorcycle round a corner and immediately realise conclusively that as Bruce Springsteen paces pavements unstaged through neighbourhoods, wastelands and riversides, his vocal track has been recorded live.

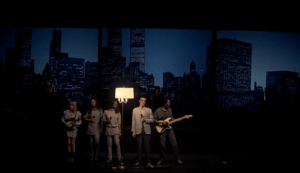

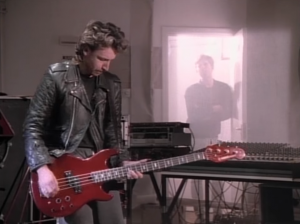

The same innate honesty shines in Demme’s breathtaking 10-minute promo for the New Order epic “The Perfect Kiss”, in which close-ups and beautiful long cuts capture the apprehension, nervousness and methodical physicality of Bernard, Stephen, Gillian and Hooky as they recite their opus across vocals, bass, guitar, cowbell, samplers and assorted drum machines and synths. The entire video is, “They play their song” – then, as now, that is artistically daring, unbelievably daring; but further building on the excitement of that audacity is another thrill, found in a filmmaking that serves to communicate the truth of those artists and that band at that time.

Furthermore, the vocal for “Streets” and the entirety of “Kiss” are original performances, which means that through Demme’s involvement, in particular the video version of “Kiss” is inherently unconventional – instead of the music video standard of hitching a radio edit to a visual accompaniment with deliberately commercial intention, Demme shoots a unique, one-time performance that subsequently stands independent as a new expression.

Jonathan Demme is in complete control of his frame. In his two most recent features, Demme paired very effectively with Declan Quinn to explore new approaches to conveying intimacy with their subjects – for Rachel Getting Married, a more obviously roving, restricted, closed-in cinema verite, and for Ricki and the Flash, a less anxious lens, opened up and relaxed.

But for the longest time, it was Jonathan Demme and Tak Fujimoto who were in complete control of their frame. Together since the Corman cheapies, these two knew when to walk and when to run and when to stand still and that all of that can happen in the same narrative, an admirable and increasingly less common commitment to plurality of camera movement clearly honoured by Paul Thomas Anderson and Robert Elswit.

In The Silence of the Lambs, consider the thrill of the sudden swooping zoom-in as Burke “brings in” Paul Krendler:

Soon after, the meticulous blocking of the phalanx of law enforcement flanking on one side Lecter and on the other Senator Martin:

And later, the precision in movement and framing during the scenes of Lecter’s escape, reminding us as an audience in 2017 that a compelling depiction of “realistic” action doesn’t have to mean a handheld camera shaking us into a seizure. I also relish Demme and Fuijmoto’s diversity of palate. The downtown fabulous vibrancy of Something Wild and Married to the Mob, Keith Haring-style reds and yellows and greens, was followed by the gorgeous, foreboding sombre earths of Lambs and the gently grave charcoals of Philadelphia.

Then we’ve the close-up. I’ve long held Demme and Spike Lee in the same stratospheric regard. Both have spent three decades moving seamlessly between feature, documentary, music video and performance film, marshaling all mediums with equal elan. Both tell white stories and black stories but seem remembered only for one or the other, never both. Both are acclaimed and yet not discussed. And both have a bravura signature shot that is seldom seen anywhere else, as though all others lack the brio to risk it: Lee has his none-more-dope double dolly while Demme’s trademark is a straight-down-the-barrel close-up, usually during shot reverse shot conversation, in which he fearlessly positions his characters centre of frame, looking right at us and speaking right to us. It’s simple, bold, arresting, idiosyncratic, I adore it.

I think Jonathan Demme resides alongside Michael Mann and Oliver Stone in a bold, specific post-Moviebrats firmament. Studio directors, perceived as commercially viable, at once regarded and appreciated and yet in a way still unheralded, still overlooked. Three thrillingly individual American filmmakers raised in the post-war boom of the American ‘50s, who on diverse paths emerged in Hollywood in the late ‘70s, who then in the ‘80s and ‘90s achieved colossal success and audience acceptance with exceptional work and without compromise of opinion or artistry. Yes, the ascent and apogee of the New Hollywood; yes, its subsequent collapse with New York, New York and Heaven’s Gate and One from the Heart; yes, “the Seventies.” But ten years later, surely Born on the 4th of July and JFK, surely The Last of the Mohicans and Heat, surely The Silence of the Lambs and Philadelphia show once again, and in more challenging market circumstances, a mainstream open to, even desirous of, a move towards the artist. Jonathan Demme did as he pleased and his films won every Oscar going.

Perhaps I can’t claim to know Jonathan Demme that well. I’ve seen Rachel Getting Married once only, with Lisa Kerrigan, at the London Film Festival, and he and Anne Hathaway and I think Robyn Hitchcock were right there. I haven’t seen any of the Corman pictures or the two that came right after, haven’t caught most of the performance films, only watched Stop Making Sense once ten years ago. I feel lucky I’ve all that still to discover. I feel lucky that I watched Rachel and Ricki and Melvin and Howard and connected so strongly after just one viewing of each. Since the advent of YouTube I’ve returned to “The Perfect Kiss” almost monthly, before that I had to dig out the tape, and did, and made Luke watch it, too. I’ve seen Philadelphia five times, six times. The Silence of the Lambs maybe 15. Married to the Mob has remained one of my all-time favourites since I was 12 years old.

There are directors whose entire filmographies I know front to back. Jonathan Demme made two dozen films but got me with only five features and two music videos, he got me. His works are an absolute blast. His range across disciplines and across genres, his creative originality, his vitality, his enthusiasm, his curiosity, his generosity, his workrate was such that I couldn’t hope to keep up. I’d much prefer it had stayed that way.

Jonathan Demme was. Jonathan Demme is.