To begin a series of decade’s end articles, the number of which will be entirely determined by our intake of port and Twiglets, Fletcher Walton remembers some of his favourite bits of the last ten years at the flicks.

“J’y vais.” – A Prophet

(Jacques Audiard, 2010)

The first sensational scene of the decade remains among its most electrifying. Across two hours, we’ve watched French-Algerian convict Malik (Tahar Rahim) patiently climb the ladder of organised crime while still incarcerated, maturing over five years from a prison punk, callow and illiterate, owned and abused, to a soldier of guile and focus, valued by all factions and primed to make big moves. Assigned an important assassination to be carried out during a routine day-release, while idling in traffic Malik recognises the opportunity for action fading fast and, in broad daylight among cafe canopies and oblivious shoppers, takes control. What follows is the most gangsta 60 seconds of European cinema this century. An icon arrived.

“I mean to kill you in one minute, Ned!” – True Grit

(The Coen Brothers, 2010)

When a redo of John Wayne’s career-capping stand-off can bring to bear the Coens reuniting with Jeff Bridges to pit him, Hailee Steinfeld and Matt Damon against a Barry Pepper baddie, shot by Deakins and scored by Burwell, you almost begin to feel sorry for the Duke. Superior filmmaking by every criteria and still among the most triumphant moments of the decade.

“He is not gonna ask you twice.” – Morning Glory

(Roger Michell, 2010)

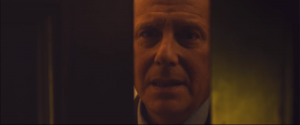

Cinematically, the 21st century has been a trudge for Harrison Ford. After the lively Hitchcock retread What Lies Beneath, Ford opened the new millennium modestly with three unmemorable misfires that set the tone for a tepid decline into increasingly obscure studio dramas and unloved big budget damp squibs, punctuated by a couple of cameos and three enormously belated sequels all of which function mainly as affable but faintly embarrassing fan service.

While waiting for Marty to call again, Robert De Niro has at least peppered his seemingly terminal slump with three roles for David O. Russell. Kurt Russell, somehow as breezy as ever, has stayed relevant by working with Tarantino and scoring a franchise. Ford has found no such patron, though it’s eminently possible he hasn’t sought one, either; what he’s served up is a dull resume the ignominy of which simply isn’t commensurate with the one-time superstar who even outside of his action-adventure wheelhouse worked so wonderfully twice each with Peter Weir, Mike Nichols and Philip Noyce.

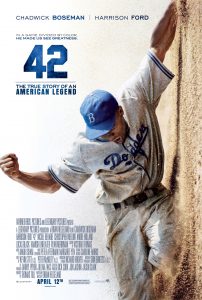

There are a couple of bright spots. 42 is a fine biopic, and Ford’s fine in it; but the best work he’s done this century is the effortlessly charming ‘80s throwback Morning Glory, in which his crotchety newscasting institution bristles against Rachel McAdams’ long-suffering but ever-optimistic gal-on-the-go producer, and it’s here we find one of the decade’s small joys, as in an act of contrition Fordy inimitably cooks (points finger) a great frittata.

“You don’t butt in line!” – Super

(James Gunn, 2011)

Bollocks to equivocation.

“I want it to mean something” – Moneyball

(Bennett Miller, 2011)

I don’t so much concede as proclaim, loudly, that my profound love for Bennett Miller’s sophomore effort thrives in symbiosis with my participation as a Fulham season ticket-holder in English football’s second-most astonishing underdog story, as my funny little team from SW6, led by a statesman of principle and wisdom and composure, in consecutive seasons first escaped relegation on goal difference with 15 minutes to spare, then snatched 7th spot to qualify for the inaugural year of a new-look international club competition, and then across a marathon 42 weeks and 19 matches marched unrelenting to their first-ever European final. With that miracle 30 months so fresh in mind, of course I saw poetic parallels between Roy Hodgson’s Fulham, an unfashionable and unfancied team made wonderful by absolute adherence to quantifiable strategies and formulas, and Billy Beane, as created by Miller and Sorkin and Zaillian and Pitt, and his rejection of orthodoxy and received wisdom and indefinables and cliché – in a word, bullshit – in single-minded pursuit of iconoclastic innovation.

“If we don’t win the last game of the Series, they’ll dismiss us. I know these guys. I know the way they think, and they will erase us. And everything we’ve done here, none of it’ll matter.

Any other team wins the World Series, good for them. They’re drinking champagne, they get a ring. But if we win, on our budget, with this team… we’ll have changed the game. And that’s what I want. I want it to mean something.”

With those words, Pitt’s Beane touches on the tragi-comic dichotomy at the heart of competition – admittedly, whatever happens this year, there’s always next season. Perhaps he identifies in the human condition the desire for greater significance we all of us seek to attach to this one relationship or that one weekend, when of course at the same time everything’s also just a procession of small events to which we choose to assign meaning. But he also defines the streak of wearied, clear-headed, quietly furious determination felt by anyone who’s ever grown to find themselves in opposition to the injustices of a bloated, dishonest institution and hoped that they possess the truth that will bring it to the ground. I want to change the game.

Coke talk – Ted

(Seth MacFarlane, 2012)

Ted: Oh look Johnny, if we’re ever gonna get serious about openin’ a restaurant, we gotta start plannin’ it now.

John: Italian.

Ted: Italian, yes.

John: What’s the special on Tuesdays?

Ted: Eggplant parm.

John: Chopped salad half price.

Ted: And it’s a non-restricted place.

John: Yeah. Wait, whaddaya mean?

Ted: Anybody can come.

John: Of course.

Ted: Jews are welcome.

John: Well yeah, I mean why wouldn’t they be?

Ted: Exactly, that’s what I’m saying.

John: Yeah, but why even bring that up?

Ted: You don’t bring it up. You just let ’em in.

John: So why mention it?

Ted: No one will.

John: So why are we talking about it?

Ted: You’re talkin’ about it, I’m just sayin’ let ’em in.

John: Yeah, let ’em in.

Ted: Exactly.

John: Right.

Ted: Good.

John: OK.

Ted: No Mexicans, though.

“Black box.” – Flight

(Robert Zemeckis, 2012)

Robert Zemeckis’ Flight boasts a scene of remarkable tension and terror in which something goes very wrong 32,000 feet off the ground and commercial airline pilot and dedicated alcoholic Captain “Whip” Whitaker (Denzel Washington) has about seven minutes to improvise a desperate response or else his passengers and the nosediving MD-80 they’re inside will make a terminal uncontrolled contact with the ground.

Overall, the scene is an interesting lesson in the continued merits of classical filmmaking form to involve the viewer as a participant. In situ, the presentation is straightforward, perhaps even flat – although the sequence is about a stupendous solution to a disastrous problem, cinematically it doesn’t feel like anything notable is happening. Its structure is so restrained that afterwards, one might even reflect with some surprise that as the aeroplane inverts, the image itself does not, and thus we are left watching everyone upside down for a full two minutes.

But in context, that bravura decision to upend the point of view is just a canvas on which Zemeckis has already worked well to assemble a masterfully layered aural collage of instrument alarms, recorded warnings, technical instructions, radio chatter and despairing human interjections as a maelstrom against which to contrast Whip’s composure – he is methodical, unhurried, confident, and utterly calm. It’s here we find the masterstroke, when Whip shows the presence of mind to advise his lead stewardess:

“Margaret, what’s your son’s name?”

“Trevor.”

“Say, ‘I love you, Trevor.’”

“What?”

“Black box – say, ‘I love you, Trevor’”

Above all else, it’s this tiny, humanising, utterly chilling moment that conclusively imprints on the viewer the abject horror of the predicament – Whip is aware he may not be able to land this plane, in which case, this is it. Every time I watch it, I lose my breath.

Late-term abortion – Prometheus

(Ridley Scott, 2012)

The one killer idea in a film that otherwise gets worse with every watch.

The climax – Evil Dead

(Fede Álvarez, 2013)

For most of its running time, Alvarez’s astute, thankfully earnest franchise reboot rides capably but comfortably on its well-worn rollercoaster track, banking corners and cresting hills without often quickening the pulse. Then final girl Mia (Jane Levy) emerges from that cabin in the woods to a rain of blood, and in a flash it’s as if the car, the rollercoaster and the theme park itself is now upside down and on fire. A horror film directed by Sam Raimi is gory and gooshy but, critically, exhilarating, hysterical and terrifying. Alvarez and his team show a strong comprehension of how to replicate that frenetic pace and sledgehammer impact within their own vivid aesthetic. “The innocent must suffer, the guilty must be punished.” A pay-off worthy of its progenitor that completely rewards the journey.

This poster – 42

(Brian Helgeland, 2013)

Jake Gyllenhaal – Prisoners

(Denis Villeneuve, 2013)

Two things elevate Prisoners from the ’90s DTV ignominy of its premise, plot and performances. The first is Roger Deakins’ unmissable cinematography – rain has rarely looked so oppressive, so bloody English. The second is Gyllenhaal’s superb turn as Detective Loki, a character so obviously of his own creation that the discrepancy is outright embarrassing to the rest of the cast. It was with this role I realised that Gyllenhaal acquitting himself is irresistible, an opinion borne out by a fantastic decade that continued with Nightcrawler, Demolition, Nocturnal Aminals and The Sisters Brothers.

Becoming – Whiplash

(Damian Chazelle, 2014)

The thrilling climax of Chazelle’s debut is among the most rewarding cinema experiences of my life, and that final kicker of a reciprocated smile between Fletcher (J. K. Simmons) and Niemann (Miles Teller), cropped tight across Simmons’ eyes to reveal at the bottom of the frame only the slightest change in his wonderfully creased countenance, is a beautiful culmination of their deliciously sick relationship. But emblematic of Chazelle’s precision and intelligence as a filmmaker is a tiny moment you may not even remember – while Andrew transcends onstage, we’re given a slow, five-second zoom close-up of his father (Paul Reiser) peering through the doors of the auditorium, mouth slack, transfixed. It looks like a shot from a horror movie – indeed, this could be Burke’s demise in Aliens. Dad is not beaming with pride or joyful in triumph. His expression is one of incredulity, concern, even a tremble of fear. What his son has become is beyond his comprehension.

Eminem cameo – The Interview

(Goldberg & Rogen, 2014)

“Oh, we forgot one – Harold Ramis, for Caddyshack, Ghostbusters and Groundhog Day” – Bill Murray, 86th Academy Awards

(2014)

If you have a bloody good friend, someone with whom you’ve laughed and loved and lived for ten years, 20 years, don’t let anything get in the way of that friendship. Don’t give time to grudges. Don’t waste time. We don’t have time to waste.

Tent – A Field in England

(Wheatley & Jump, 2014)

Yes – Culloden, Witchfinder General, The Seventh Seal. But – no. There is no preparation sufficient to diminish the all-consuming, open-mouthed awe of the sequence in which Reese Shearsmith’s Whitehead is led into a tent, subjected to something, and exits altered. Magnificent.

Friendship – Pride

(Matthew Warchus, 2014)

Dai Donovan: When you’re in a battle against an enemy so much bigger, so much stronger than you… Well, to find out you had a friend you never knew existed…well, that’s the best feeling in the world. So, thank you.

Bachmann cracks – A Most Wanted Man

(Anton Corbijn, 2014)

The unbelievable death of Philip Seymour Hoffman on Sunday 2nd February, 2014 remains an obscenity. Hoffman comes up so much when me and my pals are talking film – Scotty J, Freddie Miles, Dustin in Twister, Phil Parma, BRANDT, Lester Bangs, The 25th Hour, Along Came Polly, Owen Davian, Gust Avrakatos. It just goes on. These are roles beloved by cineastes of all abilities. Anyone who ever saw a film and has a heart.

Whenever we linger on the subject a touch too long, to move beyond the films and beyond his performances and onto the reality of thinking about him, a quiet descends, because all at the same time we’ve each arrived at the same dreadfully sad thought and it’s a thought that kills the conversation, as well it should. Reaching for any words at all, one of us will muster something like, simply: “There should have been more.”

When I took my seat for A Most Wanted Man, Sunday 21st September 2014, I knew that there was no more – beyond lending support in two more installments of The Hunger Games, this was the last thing Phil would ever get to tell us. In five years, I haven’t watched the film again. I wonder if I want to keep that experience separate. What I recall of Hoffman’s stoic intelligence operative Günther Bachmann is a man of inadvisable dedication and physical dilapidation, with a self-negating, almost masochistic emotional control. That control is relinquished only once, briefly, furiously, justifiably. It is an eruption in reaction to the apparent impossibility of catharsis and in Hoffman’s hands it is harrowing, maddening, saddening, bracing, brilliant.

The kill – Gone Girl

(David Fincher, 2014)

Every minute spent bringing this project from novel to screen is justified by affording Fincher, Jeff Cronenweth, Kirk Baxter, Rezner & Ross and Rosamund Pike the opportunity to create this.

Roger Deakins – Sicario

(Denis Villeneuve, 2015)

After 30 years in feature films, Sir Rog spent the entire decade in God mode. Working sparingly, he appeared to accept each project as an opportunity to select for himself some utterly implausible personal challenge, and then proceed to take the piss – a single-shot war film in 1917, Skyfall‘s absurd neon fight scene, every frame of Blade Runner 2049. The jaw-dropping – jaw dropping – sequence at dusk in Sicario is another ridiculous feat of improbable beauty, and sat in the cinema overwhelmed with admiration I gazed in awe and audibly, half-laughing, said simply, “Fuck off.” Deakins was already marvelous by the end of the ’90s – 20 years later, his unsurpassed ability has reached a level where it is reforming cinema, and he still has more to show us.

“We’re not ugly people” – Carol

(Todd Haynes, 2015)

Well, I cried.

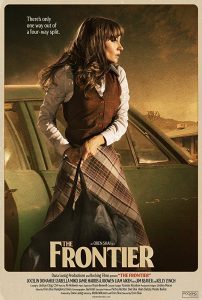

This poster – The Frontier

(Oren Shai, 2015)

This feller – Star Wars: The Force Awakens

(J.J. Abrams, 2015)

“Pretty” Ricky Conlan’s ring walk – Creed

(Ryan Coogler, 2015)

For me, this was the moment a new talent announced himself. Exciting doesn’t cover it – Coogler showed me something I never knew I needed and now couldn’t live without.

The ending – Hyena

(Gerard Johnson, 2015)

Because how else could that end?

Rodrigo Prieto – Silence

(Martin Scorsese, 2016)

“Love My Way” – Call Me By Your Name

(Luca Guadagnino, 2017)

Clothes, tunes, exploits, weather – the perfect evocation of my dream holiday, and it’s even set in the early ’80s.

That final shot – Dunkirk

(Christopher Nolan, 2017)

No, not that.

This:

“General anaesthesia” – The Killing of a Sacred Deer

(Yorgos Lanthimos, 2017)

Delightfully honest and wrong.

Henry Cavill’s moustache – Mission: Impossible: Fallout

(Christopher McQuarrie, 2018)

In some important ways I thought Cavill’s performance was borderline dreadful – every line reading a wrong one. But physically, aesthetically, in the wardrobe choices and, above all, with that notorious ‘tache – perfect.

Strodes unite – Halloween

(David Gordon Green, 2018)

Satisfyingly, there is immense power in three generations of Strode women working as one to dispatch their tormentor because director David Gordon Green created that power through his filmmaking. He didn’t rest on decades of mythology or series expectations or the goodwill of fans – he arrived at a convoluted franchise, already the subject of a reboot and a pair of remakes, and sculpted a movie that made sense in and of itself. It earns its emotional pay-offs not from 40 years of history but on the strength of its execution. The antidote to Star Wars VII.

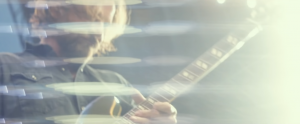

“Black Eyes” – A Star Is Born

(Bradley Cooper, 2018)

Thematically, the standout moment arrives at the Grammys hack rendition of “Pretty Woman”, and the self-indulgent, obnoxious, beautiful, desperate howl of sad, superfluous masculinity Jackson Maine (Bradley Cooper) screams with a single sustained note from his Gibson. Cinematically, the film never bests its perfect opening – how could it? – and those two minutes belong to DP Matthew Libatique, whose unrivaled evocation of live performance, with horizontal lens flares like a fretboard leaping into the audience, intensifies the spectacle ten-fold to create pure, immediate, foot-stamping joy.

All the escapes – The Old Man and the Gun

(David Lowery, 2018)

“Polina’s back!” – The Death of Stalin

(Armando Iannucci, 2018)

Michael Palin’s portrayal of Old Bolshevik Vyacheslav Molotov was his first onscreen role in 20 years and he is magnificent. His Molotov is a lovable greying revolutionary now sentenced to obscurity – if he’s lucky – whose calm devotion to Stalinism is so total he refuses even to condemn the suspected abduction and execution of his own beloved wife. The horrific absurdity of this national condition – cognitive dissonance as the only means of preserving sanity, liberty and life – plays out in microcosm during the farcical scene in which Molotov’s wife is unexpectedly returned alive – before which, Molotov, Khrushchev (Steve Buscemi) and the diabolical Beria (Simon Russell Beale) must warily circle one another with propagandist rhetoric, each man desperately second-guessing the thoughts of the other two, afraid to be the first to publicly not denounce the non-traitor. Draw parallels to our culture’s contemporary recriminatory purges and circular firing squads as you see fit.

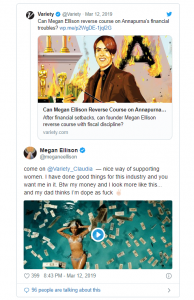

This tweet

(Megan Ellison, 2019)

Jennifer Lawrence – Silver Linings Playbook, American Bullshit, Joy

(David O. Russell, 2012, 2013, 2015)

How many of the most engaging, or exciting, or exhilarating moments of the last ten years of American cinema have been brought to us by Jennifer Lawrence? With which other precocious onscreen talent can we even begin to draw comparisons? Is it only Eddie Murphy? Because when she assumes control of a scene, as in Silver Linings Playbook and American Bullshit and Joy, and proceeds to verbally boot every man standing in the balls, Lawrence – not yet 30! – is very much the new sheriff in town. By her third outing with David O. Russell, in my filmgoing household the Lawrence takedown had already achieved anticipatory status. As we wait in nervous rapture for Ripley, for Cliff Booth, for B-Rabbit, for Ah Jong and Li to flip the switch and blow the roof off, so too do we nudge each other with pre-emptive excitement as, finally, after frustrations and irritations and the incompetence of others have reached boiling point, Jennifer Lawrence turns to face her haters and absolutely, positively kills every motherfucker in the room.

BlacKkKlansman

(Spike Lee, 2018)

Further reading: a long, long list of our favourite people of the decade, and, finally, our favourite films of the ’10s. See you in ’20!