OSS20-0519/0612FW103 – From the Files of O.S.S. – No Short Cuts: The O.S.S. Guide to Streaming Films in the UK

Supplementary to our forthcoming discussion on The Evening Glass, in which comedy’s Aidan McCaffery insists streaming films is the bee’s knees and physical media proponent and laserdisc collector Fletcher Walton ain’t so sure, One Sensational Shot presents its findings on the state of streaming in the UK in 2020 and considers what streaming means for people who like watching films. Don’t junk your DVDs just yet!

Does The Gravy Train exist? Also known as The Dion Brothers, The Gravy Train is a now legendary 1974 knockabout crime comedy by Jack Starrett, co-written by Terry Malick, starring Stacy Keach and Frederic Forrest, beloved of Tarantino, deeply influential on David Gordon Green’s Pineapple Express, and unavailable everywhere except YouTube, where uploads appear from time to time, and the literal celluloid reels of its original release. No VHS, no laser, no DVD, and certainly no legal streaming.

Like Tom Schiller’s similarly unobtainable Nothing Last Forever, The Gravy Train is fetishized for its scarcity and perhaps overrated because of it – its inaccessibility is definitely part of its appeal. The flip side is that if nobody watches the fucker, it will eventually be forgotten. Put in these terms, it’s easier to empathise with all those nerds in a flap about getting their Original Trilogy on Blu Ray.

This issue is among my principal concerns with online streaming and accessibility of cinema in 2020 – what is available to stream, and how available is it? If a film is not available, how will it be watched? If it is seldom watched, at what point is it functionally extinct? Who controls what we can watch? To what extent are they working in the interests of cineastes and of cinema?

A month ago, what I didn’t know about watching films online could just about fit into Cheddar Gorge. I’ve streamed one movie – in January 2019, I caught Happy New Year, Colin Burstead on the iPlayer before it disappeared for a while. And the other week I watched The Gravy Train on YouTube again, cos with all this Covid about I can hardly step over to Quentin Tarantino’s pad to watch his print, can I?

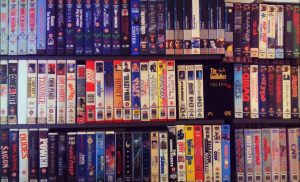

In my home at least a thousand films across four formats fill a bookcase and a knock-off Kallax and wooden storage cubes and oblongs I bought unfinished and varnished myself. (This mass of stuff reflects a love of cinema, but I’m cognisant my passion for collection and curation is also an expression quite separate from enjoying movies, and one I certainly wouldn’t encourage in others.)

Added to that I’ve another 50 pictures saved off the telly to the hard drive on the Virgin box, and 50 more on the Toshiba DVD-VHS-HD combi. Consequently, I’ve long felt that before I toss hard-earned pennies at 21st century ones and zeroes, I should rather play with the toys I’ve already got.

Additionally, there’s Film 4, and ITV4, and Talking Pictures, and an alternating choice of Clint Eastwood or Steven Seagal or The Fugitive/US Marshals on TCM, and whatever you can make out through the blurred, tawny patina of the (sub) standard definition broadcast of Sony Movies (though the snips of their censorship scissors render many pictures less watchable still). A free-to-air choice of a dozen films a night, every night for everyone who owns a telly always seemed like enough to be getting on with.

For all those reasons, I don’t know much about streaming, so I started at the beginning.

Who’s out there streaming, and what’ve they got?

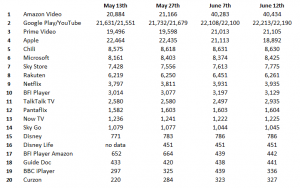

Three services boast libraries of more than 20,000 films*, and to my surprise none of them are called Netflix. The big dogs are Apple iTunes, which rents and retails individual films; Google Play/YouTube, which also rents and retails individual films; and Amazon, which across four marques rents and retails individual films and also offers subscription services.*

*To my astonishment, in the four weeks between beginning research and publication, Apple has lost 3,500 titles, busting it down below 19,000, while Amazon’s library has doubled to 40,000. I don’t know how this can be accurate. Unless Amazon just acquired the nation of Italy, I presume Just Watch is counting titles twice.

Apple is Apple, a single service through iTunes with which even I’m familiar. Google Play claims a few dozen more titles than YouTube, and they are ostensibly separate services, but in practice they share identical price points, availability and functionality.

Amazon offers four streaming services of varying depth. Prime Video is one of several features included with Amazon Prime membership (£79.00/year, or £5.99/month), so functions as a subscription service. Amazon Video rents and sells titles, many of which will also be available to Prime subscribers as part of their membership. BFI Player on Amazon is a £4.99/month subscription service through Amazon which largely – but not completely – replicates the much larger library of the BFI Player in a snapshot one-fifth the size, and is of particular utility to those cats who watch everything through their games consoles. And there’s also StarzPlay, which functions principally as Amazon’s Netflix-style television network but still offers a few films (seemingly TV movies) that Prime and Video do not.

The second strata of VOD providers each offer 6,000-9,000 films. They are boutique newcomer Chili, and the more familiar names of Microsoft, Sky Store, and Rakuten. All four rent and sell only.

The inventory of subscription streaming goliath Netflix (£5.99-£11.99/month) is a comparatively miserly 3,900 titles, an important reminder that it cares a lot about television and a lot less about cinema. Next comes the BFI Player (£4.99/month), a more specialised subscription service, comprising a little over 3,000 films, followed closely by TalkTalk TV’s Sky-style broadband-subscriber provision, with a little under 3,000.

A further clutch of three – Pantaflix, and the Sky-affiliated Now TV and Sky Go – offer 1,000-1,600 titles, and another dozen providers, now including Disney and Disney Life, hold fewer than 800.

Libraries change almost daily, and the rate of that change surprised me, so presented below are figures approximately correct at date of publication, and figures for one, two and four weeks ago, when I began the research.

Focusing on the largest libraries, across rental most titles are available at either 2.49 or 3.49. All Chili rentals are 2.49, which always makes them among the cheapest options; Amazon’s price is usually only beaten by Chili; Google Play/YouTube are rarely cheaper than Chili and Amazon; Apple is always among the most expensive; and Microsoft, Sky Store and Rakuten generally track Apple. On retail, Apple fared better – usually cheaper than Google Play/YouTube, but usually beaten by Amazon.

A long digression about rental streaming

Rental loses me entirely on value for money and return on investment. Even 20 years ago, in the pomp of Blockbuster’s inglorious reign, paying 1.50 per night didn’t make sense when you could rent from the local library for half the price and a week at a time. Back then alternatives were few. Today they are plentiful.

From my own esoteric old tech perspective, streaming a film to watch once costs a quid or two more than buying it on VHS tape and a quid or two less than buying it on laserdisc – but a paid-for rental digital stream, and for that matter a paid-for retail digital download, comprises no capacity to claw back that cash, whereas a tape or a laser can easily be resold, for the same money or more. At current prices, a tenner bound for Bezos gets you only two or three films; a tenner spent on two or three tapes or a couple of lasers can be recouped with the resale of those items, spent again on more, recouped again, and on and on indefinitely, like some enchanted coin in a folk tale.

Without question, the fidelity of a stream – if the internet connection holds and if it’s viewed on a decent telly rather than a tablet or an old laptop or a damned phone like you’re Tom Hanks in Dragnet – will represent a tremendous viewing improvement over a tape or a laser, probably an appreciable improvement over a DVD, and plausibly even a Blu Ray.

But it’s a single-viewing rental. What value for money does that improvement in sound and picture quality represent to a consumer in a market where 3.49 can be spent on 1) one HD stream, or 2) literally five or six second-hand DVDs?

DVDs have become an absurdly undervalued resource to cineastes. ‘00s releases overflowing with commentaries and production documentaries, double-disc sets and special editions, are available for pennies. Luke will hit CEX on a lunch break, grab a bagful of titles for less than a fiver, rinse the special features over a weekend, and the next fortnight whatever he doesn’t want to keep goes to the charity shop. Does accessing a 1080p stream of Inception beat accessing 720p DVDs of Inception, Memento, Insomnia, The Prestige and The Dark Knight for the same price?

Streaming putatively represents increased accessibility and convenience – everything*, everywhere**, now. But to what level and for whom is that convenience meaningful, or helpful, or desirable? In practical terms, portable access to 20,000 films you may want to watch is no more useful than portable access to 20 films you will want to watch – these bastards still have to be viewed one at a time, and a choice greater than a few dozen is paralysing.

Selecting a film while sat at home and then streaming it would appear to “save time” – but to what extent is that saved time meaningful? Does ten minutes in Oxfam every other weekend really represent an inconvenience? Is a modicum of forward planning truly so burdensome? Throughout the ‘90s, did those less able to leave the home – parents with babies, the infirm, the elderly, the very lazy or very stoned – sit in their living rooms and simply expire from boredom, until the invention of Netflix?

(Ironically, when the UK’s response to Covid-19 created the precise set of unprecedented restrictions that made streaming more useful than ever – that is to say, everywhere was shut and we couldn’t go out – unsurprisingly, Netflix and other services conceded to legislative recommendation and voluntarily reduced their streaming rates and quality, thereby diminishing their competitive advantages in fidelity and accessibility.)

Yeah, but Fletch, nobody pays rental

And, though it renders half the preceding eight paragraphs redundant, thank fuck for that. The subscription model, as offered by the BFI, is where the action’s at.

A second digression, about how streaming impacts accessibility

In the broadest generalisation, streaming would appear to have made cinema more accessible. In rural areas with dependable broadband, it undoubtedly has – although it should be remembered that the cattle barons of Amazon and Netflix were the very forces responsible for driving off all alternatives to streaming.

I also shan’t overlook that a typical video store, no matter the depth of its library, kept very limited numbers of each title, like Movie Magic at Park Merced (don’t look for it; it’s not there anymore) and its single precious VHS of Lizzie Borden’s Born in Flames. Disappointment lurked. Wait lists ran long. Gratification was delayed or denied. Rental is now a simple egalitarian binary – either it’s online, so you can watch it regardless of how many others are at that exact moment doing the same, or it isn’t online, so you can’t watch it at all.

But in towns and cities, where during the 1980s and 1990s cinemas, video rental outlets, retail video chains and independents, public libraries, college libraries and university libraries made film more available than ever, access to movies has arguably remained almost constant. It’s now superficially quicker, but only if you want to pretend that stepping into a library or a video store had to be its own onerous activity rather than a ten-minute errand one or two days a week on the commute home from school or work. In the 20th century, some people even found spending time in a shop enjoyable (imagine!)

Critically, the last 15 years, which witnessed the overlap between physical renting and streaming, may represent a high-water mark. Continuing a half-decade upward trend, 2018 and 2019 were the biggest years for cinema attendance in half a century (177,000,000 admissions and 176,100,000 admissions, respectively) but the UK’s response to Covid-19 will have fucked that. Physical rental is functionally extinct; physical retail, plummeting in popularity, has largely migrated online, and to the supermarket on the shelf by the checkout; public libraries have been ideologically underfunded. There’s never been more films to buy and there’s never been more films to watch on telly. But as far as rental and subscription by streaming goes – and for a decade, consumers have been encouraged to reject ownership to the extent we’re edging closer to rental and subscription domination – home cinema now rests almost entirely in the hands of a dozen services.

Half of these services have little credible historical connection or commitment to film; most of them have no dedication to curation or preservation; and some of them – for instance, Netflix – are founded on a purely commercial ideology driven to replace and ultimately exclude existing titles and their attendant licensing expenses – that is, one hundred years of cinema – with new “content” created by the platform, usually for its exclusive use. (Thank the stars Criterion have begun sorting us out with another way to watch some of these pictures.)

These services are happily beholden to the mass market – the critical determinant in whether you can watch Billy Friedkin’s To Live and Die in LA may well be how many other people want to watch it, too.

I’m dismayed by the extent to which these services could be subordinated to Twitter mobs, which in the four weeks between writing that clause and publishing this article has proven to be well-founded. Netflix will happily adhere and acquiesce to the whims and trends of young consumers in order to keep its hand in their pocketbooks – nuance, discretion, context, fairness and facts will be eagerly sacrificed at the altar of commerce. And I’m also suspicious about the susceptibility to political interests – although the absences of The Last Emperor and Kundun and Farewell, My Concubine is probably just a coincidence.

And as with any tech disruption, the success of the big (loss-making, tax-avoiding) streaming services – driven in part by the public’s baffling enthusiasm for swallowing the argument that a 120 mm disc, though demonstrably superior to streaming, is disposable, bulky and redundant – has eliminated immediate competition (virtually every video store in the country lost inside ten years) and now threatens to eliminate similar alternatives. A taxi on a ride-sharing app is cheaper than a black cab until there are no black cabs, then that ride-sharing app will set whatever price it chooses. When manufacture of physical media and the means to watch it is depressed even further, what’s to stop a streamer tripling the price on everything?

What’d you do?

Using Just Watch, I researched the availability of more than 500 feature films. Presuming from the outset an excellent provision for 21st century cinema and a much poorer selection for anything older than Julia Roberts, I chose to found my investigation in the happy medium of popular American cinema 1970-1990 – these films are certainly old and older, but they’re almost all mainstream A- and B-pictures boasting familiar talent. To expand and add balance, I also included every winner of the Palme d’Or since 1960, every winner of the Academy Award for Best Foreign Feature since 1960, and every Best Picture winner since the Academy Awards began in 1929. And, once I’d done all that, I looked into a few other things, too.

What’d you find out?

I found out that Just Watch, though useful, is not infallible, so regrettably, while my data is understandably subject to the vicissitudes of licensing agreements, there are also instances where Just Watch was just wrong, necessitating time-consuming cross referencing that Just Watch was surely created to avoid.

Apple’s library was the broadest, but has been supplanted by Amazon over the course of May and June. The vast inventory of Google Play/YouTube seemed to offer the fewest titles unique to its service (if any), while the much smaller libraries of Chili and the BFI proved notably diverse, allowing them to punch well above their relative size.

Chili held plenty of well-known and worthwhile Hollywood films unique to its service, including Less Than Zero, Bob Roberts, Girl 6 and Blood and Wine. The BFI reflected a similar level of exclusivity among arthouse pictures but could even boast lauded mainstream fare such as Fosse’s Cabaret and Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows.

Pantaflix offers a plethora of films not available elsewhere – though in this case, that means many, many obscure European films and various Charles Band action cheapies of divergent quality and renown.

Netflix offered less than 10 per cent of the 500-plus titles I surveyed – in the context of my search, it was an irrelevance.

So, all told, the order of usefulness ranks Amazon Video, then Apple, with Chili and BFI Player sharing bronze. I know Bezos is a gazillion dollars lighter since the divorce, poor thing, but relative poverty notwithstanding I shan’t recommend more money spent in his direction, so you should be sorted out by a subscription with the BFI supported when necessary by a rental from Chili.

Here’s a few of the pictures unavailable online that streaming apologist comedy’s Aidan McCaffery doesn’t want you to see…

Twenty-nine per cent of James Cameron’s seven feature films

Or 25%, if you count Piranha II. Both The Abyss and True Lies are still hard copy only, and hilariously the hardly prolific Big Jim says the reason he hasn’t got round to an HD release of the former is that he “hasn’t had time.” Stick with your Laserdiscs.

Twenty-five of the movies which have won the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film since 1960

Including Closely Watched Trains, Z, Day for Night, 2001’s No Man’s Land, 2003’s The Barbarian Invasions and 2008’s Departures.

Twenty-five Palme d’Or winners in the same period

Twenty-five of the last 68 winners, including The Tin Drum, Farewell My Concubine and Fahrenheit 9/11, are not on any platform, and a further 14, including If…., The Conversation, All That Jazz, Secrets and Lies and Dancer in the Dark, are currently available on only two services or fewer.

Sixteen ‘70s essentials

Melvin van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

Hopper’s The Last Movie

Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop

Carnal Knowledge by Mike Nichols

Schlesinger’s Sunday Bloody Sunday

Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs

Rafelson’s The King of Marvin Gardens

The Mack by Michael Campus

Richard Rush’s Freebie and the Bean

Let’s Do It Again by Poitier

Inserts by Byrum

Bound for Glory by Hal Ashby

Peter Yates’ Mother, Jugs & Speed

Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky

Scorsese’s New York, New York

Gillian Armstrong’s My Brilliant Career

Fifteen hours of the finest auteur work of the ‘80s (and a couple by Cimino you have to watch as well)

Thief and Manhunter by Mann; Melvin and Howard and Something Wild by Demme; One from the Heart and The Cotton Club by Coppola; The Brother from Another Planet by Sayles; To Live and Die in L.A by Friedkin; and The Year of the Dragon and The Sicilian.

Seven Best Picture winners

1929’s The Broadway Melody and 1937’s The Life of Emile Zola, but also Rebecca and The Best Years of Our Lives from the 1940s, Gigi from 1958, and, remarkably, The Last Emperor and Dances With Wolves.

Six Cannon releases well worth watching

Ninja III: The Domination

Breakin’

Love Streams

Street Smart

52 Pick-Up

Godard’s loopy King Lear

The first three films by Keith Gordon

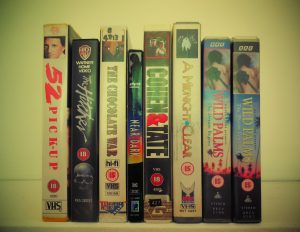

Keith Gordon’s superlative opening triumvirate – Static, directed by and co-written with Mark Romanek; and his two efforts as writer-director, The Chocolate War and A Midnight Clear – are unavailable to stream in the UK, and you shan’t find his work on the Oliver Stone mini-series Wild Palms, either. Thankfully, and in stark contrast, Gordon’s three most recent feature films before moving to episodic television – Mother Night, Waking the Dead and The Singing Detective – are all readily accessible across at least five, six and seven platforms, respectively. You’ll do well to find Static on any format, but you can pick up A Midnight Clear here.

And the first three films by Eric Red

Eric Red established his cult writing three sparse, inventive, sophisticated and shocking nightmares of the American road – The Hitcher, directed by Robert Harmon; Near Dark, directed by regular collaborator Kathryn Bigelow; and Cohen and Tate, which he directed himself. Surprisingly, none are available to stream. Though the rest of his cinema releases are well represented, this is like going to rent Taxi Driver and returning home with Bringing Out the Dead.

Two of the best teen movies ever

The Sure Thing and Better Off Dead. And since we’re discussing early Johnny Cusack, you also won’t find Grandview, U.S.A. or Hot Pursuit, and The Journey of Natty Gann has just been ringfenced by Disney.

And – but of course – Robert Altman’s Streamers.

But, here’s a handful of obscure gems that thankfully can be found online…

Mann’s The Keep, unavailable on DVD anywhere but Australia

Susan Skoog’s Whatever, still virtually unavailable on DVD

both Suburbia by Penny Spheeris and SubUrbi@ by Dick Linklater

Bill Murray’s third-best film, Quick Change (relative to its scarcity on television over the last 30 years and the peculiar absence of a Region 2 DVD release, Quick Change might reasonably be considered the most available film online)

Kevin Reynolds’ The Beast of War

Kelly Reichardt’s River of Grass

Donald Cammell’s White of the Eye

Seven interesting things only available on Chili:

The Hot Rock

The Panic in Needle Park

Next Stop, Greenwich Village

The Electric Horseman

The Five Heartbeats

Girl 6

American Movie

(When I began my research, The Great Santini and Wise Blood were only on Chili, now both are also available on Amazon.)

Six interesting things only available on BFI Player:

Akenfield (Luke and I quote this to each other more than Star Wars)

El Sur

The Missionary

Made in Britain

Orphans

The Edukators

(When I began my research, Frances Ha and Upstream Color were only on BFI Player, now both are also available on Amazon.)

Five interesting things only available on BBC iPlayer

The Wooden Horse

Curtis Hanson’s Bad Influence

Raimi’s A Simple Plan

The Fear of God: 25 Years of The Exorcist

Primary Colors

(I did have five interesting things only available on BFI Player Amazon but three weeks later, Dr Mabuse The Gambler, Westfront 1918, A Touch of Zen and Straight to Hell are no longer available – on BFI Amazon or anywhere else – while The Bad Sleep Well has stayed on BFI Amazon but also turned up on BFI Player, as has the majority of Kurosawa’s filmography.)

And… Stephen Frears’ transcendent second feature The Hit, starring Terry Stamp, John Hurt and Tim Roth, is available only on… Britbox!